Black communism in the Great Depression

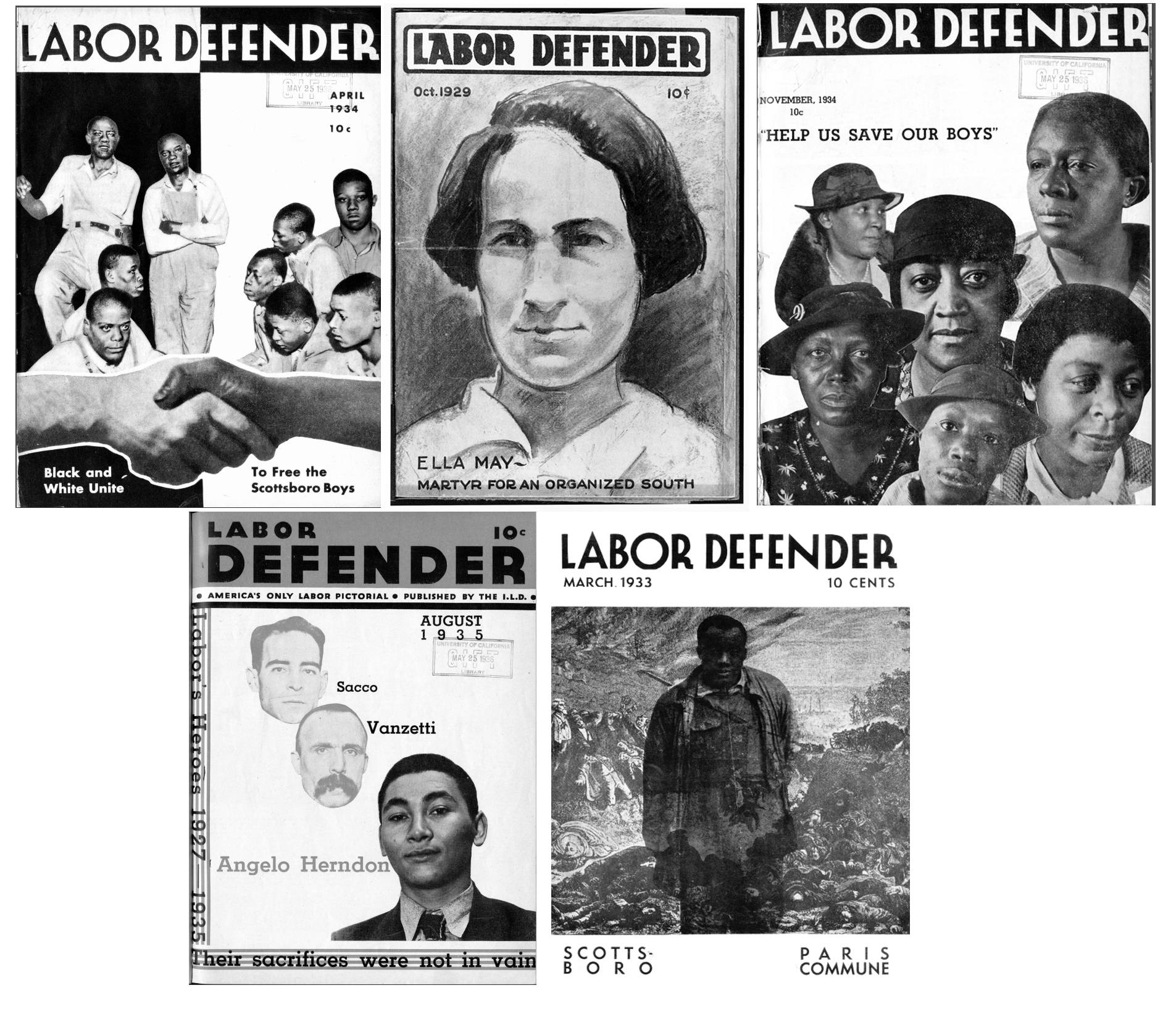

Angelo Herndon joined the Communist Party in 1930 in the depths of the Depression and Jim Crow segregation. The Black son of a coalminer, he had left home at 13 to work in the coalmines of Kentucky. Four years later, he was a Communist union organiser. After organising a desegregated protest against unemployment, he was arrested and soon charged with “inciting to insurrection”—a charge that brought the possibility of execution. Convicted and sentenced to twenty years on a chain gang, Herndon was ultimately freed after a successful appeal by the Communist-organised International Labor Defence—and became a celebrity worker-militant, giving speaking tours around the US.

Ella May Wiggins was a white single mother of eight children. She worked twelve-hour days in a textile mill in Loray, North Carolina. When the Communists showed up to help organise a strike, she was at the forefront. Through her involvement in Communist-led worker activism, she became famous for her leadership and her ballad-writing skills. One of her songs went:

We’re going to have a union all over the South,

Where we can wear good clothes, and live in a better house.

Now we must stand together, and to the boss reply,

“We’ll never, no, we’ll never, let our leaders die.”

She was also known for her commitment to desegregated organising, uniting Black and white workers—and for that she was murdered by company stooges in September 1929. Her children were taken straight from her funeral to an orphanage.

● ● ●

The Great Depression shook the United States to its core. Old certainties were shattered as millions of workers saw their desire to live a decent life broken on the wheel of capitalism’s boom and bust cycle. In that maelstrom of despair, anger and bitterness, the Communist Party of the United States organised some of the best of the resistance.

The Communist Party was the first organisation on the US left really to see fighting racism as a central task. It made a substantial advance from the position of the brilliant socialist leader Eugene Debs, who, despite a solid personal track record of opposing racism, had argued that socialism “had nothing special to offer the Negro, and [socialists] cannot make separate appeals to all the races”.

The advance of the Communists came partly at the prompting of the Communist International (Comintern), the alliance of revolutionary parties established to spread the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution. In the early 1920s, Lenin had chastised the US party for not undertaking more work to recruit Black workers and campaign for Black rights.

During the 1920s, a few Black activists became attracted to communism. Cyril Briggs led an organisation called the African Blood Brotherhood, which organised self-defence against racist assault. Inspired by the Comintern’s militant anti-colonialism, and in response to the race riots that swept the country in the summer of 1919, Briggs joined the Communist Party, along with most of the Brotherhood leaders.

In 1928 the Communist International held its Sixth Congress, a turning point in the movement’s history. This congress marked the culmination of Stalin’s struggle for power within the International, and the adoption of the perspective that the world had entered a “Third Period” of capitalist crisis and imminent global revolution, which in practice meant that Communist parties engaged in frenetic, apparently ultra-militant activity, while denouncing their rivals and internal oppositions as fascists. At the same time, the congress passed a resolution calling for “the right of Negroes to national self-determination in the Southern States where the Negroes form a majority”.

Historians agree that the policy, turned into the slogan of “self-determination for the Black Belt”, was not much used in the party’s day-to-day work. But it did have a major impact on the Communist Party in two ways: it pushed the party to emphasise organisation of Black workers, and it drove the party into the southern states.

● ● ●

In late 1928 the party began an organising campaign in the textile mills of Gastonia, North Carolina. The party had recently set up the National Textile Workers Union. The plan was to organise mills in the southern state of North Carolina before the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had a chance to do it first. When the organising campaign began, there was no mention of the “Negro question”, but by the end of it, the issue had become central.

Fred Beal was the party organiser sent to Gastonia. He launched a poorly organised but heroic strike. Despite immediate repression, the strikers held out for months. As it unfolded, the Comintern sent two organisers to Gastonia: the 29-year-old Albert Weisbord, who had led a major textile strike two years earlier in Passaic, New Jersey, and the Black leader Otto Hall. Hall and Weisbord would insist that the party begin seriously organising Black workers.

The Great Depression fertilised the soil the party was attempting to sow. There were four main sites of organising among Black communities: the south, northern cities, the Scottsboro campaign and the new mass unions.

● ● ●

The CP began its push into Birmingham, Alabama, early in 1930. Within weeks, a member had his house firebombed. That didn’t deter the party. They began organising in the steel mills around the city. Soon they established unemployed councils to lead demonstrations that at their heights gathered around 5,000 protesters, standing up to violent repression from the police. By 1931 the party had built an activist core of Black workers. By 1935 the party had 2,000 members in Alabama. Ninety per cent of them were Black.

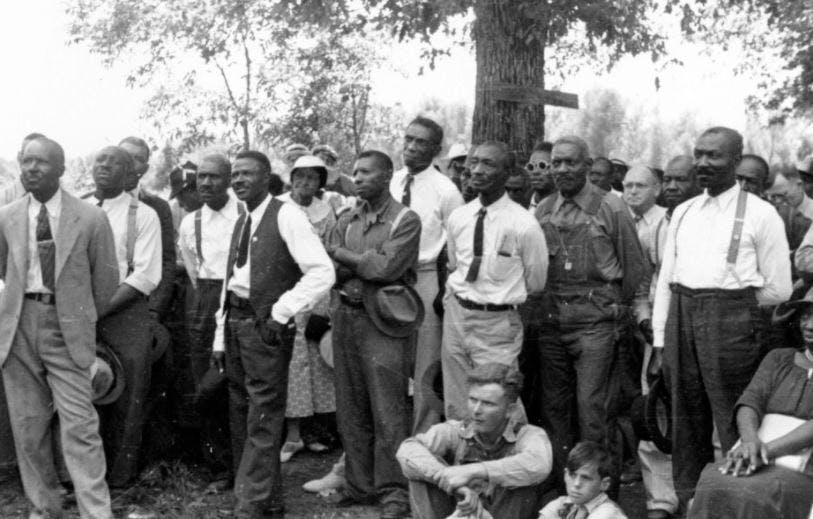

Sharecroppers—poor, mostly Black tenant farmers who didn’t own land—were hit hard by the Depression and a plague of the cotton-killing boll weevil. Following a rebellion by sharecroppers in Arkansas, the Communist Party’s southern paper, the Southern Worker, began receiving appeals for assistance. The party sent two organisers, Mac Coad and Al Murphy, who made contact with two local Black militants, Ralph Gray and his brother Tom. They established what would soon become the Sharecroppers’ Union (SCU). The Grays’ grandfather had been a state legislator during Reconstruction, the brief period following the Civil War when it seemed like social and political equality could be achieved for southern Blacks.

The memoirs of those who joined at the time give a sense of what the party meant to its members. “All my life I’d sweated and [been] stepped on and Jim-Crowed”, Angelo Herndon recalled. “I lay on my belly in the mines for a few dollars a week, and saw my pay stolen and slashed, and my buddies killed. I had always detested it, but I had never known that anything could be done about it. And here, all of a sudden, I had found organizations in which Negroes and whites sat together, and worked together, and knew no difference of race or color. It was like all of a sudden turning a corner on a dirty, old street and finding yourself facing a broad, shining highway.”

Hosea Hudson was a Birmingham steelworker . The Communist Party taught him to read. When Al Murphy asked him to an unemployed council meeting, Hudson remembered his grandmother’s words: “I thought for a minute of my grandmother saying the Yankees were coming back to finish the job of freeing the Negroes in the South. Every time there was an attack on my people I wondered when that day would come”.

One of the defining themes in these workers’ political world view was the completion of the project of Reconstruction. James Allen, editor of the Southern Worker, wrote that the issues of equal rights and land “have been presented for revolutionary solution before. They were the core of the period of Reconstruction ... The issues left unsolved by a previous revolution have been taken to the bosom of the modern, proletarian movement”.

Women played an important role in the organisation of sharecroppers by the Communist Party. The daughter of a sharecropper, schoolteacher Estelle Milner, began secretly distributing union leaflets and copies of Southern Worker throughout the county. The police would later beat her so badly they broke her back.

Ralph Gray was murdered at Camp Hill in 1931. His death was part of a wave of anti-union violence that murdered or drove others out of Tallapoosa. The survivors regrouped and continued organising. From late 1931 until May the following year, Gray’s 19-year-old daughter Eula became the ad hoc secretary of the Sharecroppers’ Union. By 1935, SCU membership exceeded 10,000.

But the party’s work in the south was to be badly damaged by the so-called Popular Front perspective adopted in the middle 1930s.

For Stalin’s Comintern, the late 1920s had been the ultra-militant “Third Period”. Separate campaigns and unions were the order of the day. But in 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany, and Stalin’s government sought to stabilise relations with capitalist countries. An abrupt about-turn was introduced. It became known as the Popular Front. Communist Parties were instructed to subordinate themselves to reformist and bourgeois forces. In the US, that meant Communists subordinating themselves to the Democrats, led by President Roosevelt.

The sectarian approach of the Third Period hadn’t badly damaged the southern Communists: there, they were the only force really trying to organise working-class Blacks around economic demands, so sectarianism didn’t make much of a difference. But the new Popular Front line was fatal to Black southern Communism. The party sacrificed its role in the Black working class to pursue right-wing Democrats.

In 1937, supposedly forging an anti-fascist alliance with “democratic” bourgeois forces, the party endorsed for Congress Alabama Democrat Lister Hill—a man who opposed anti-lynching legislation. The Communist Party dissolved the Sharecroppers’ Union into two predominantly white, AFL-affiliated organisations. The Southern Worker was dropped and replaced with New South, a “Journal of Progressive Opinion” designed to attract southern liberals. By 1943, there was not a single party organisation in the south left.

● ● ●

The centre of the party’s work among Blacks was Harlem in New York. The Communists had recruited significant intellectual and activist figures through the 1920s and set up the small American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC). Richard Moore, an early recruit, took over leadership of the ANLC at the end of 1927. The following year he established the Harlem Tenants League.

It was a good move: the ANLC had focused on union work, but racism in the AFL had meant Black workers were not very receptive to unionisation, and the AFL stymied a few small efforts to organise Black workers. Until the labour upsurge after 1934, the northern Communists had better luck with campaigns outside the point of production: tenants’ rights, solidarity with the Scottsboro defendants, sit-ins at welfare offices, rallies against discrimination in education and cutbacks in the Works Progress Administration employment programs.

At its height, the CP had nearly 1,000 members in Harlem. In contrast to the southern experience, membership peaked after the Popular Front. In the Third Period, the party was hamstrung by its sectarian attitude to the Black reformist, liberal and nationalist groups. These forces had deep roots in the community, and their authority wasn’t shaken by the CP’s denunciations of them. The Popular Front helped the party gain members, allies and sympathisers for a period, but at the expense of a distinctly Communist line.

Still, the CP was known for being a racially integrated political organisation. That won it support from northern Blacks in the 1930s. Nothing did more for that reputation than the party’s defence of the so-called “Scottsboro Boys”.

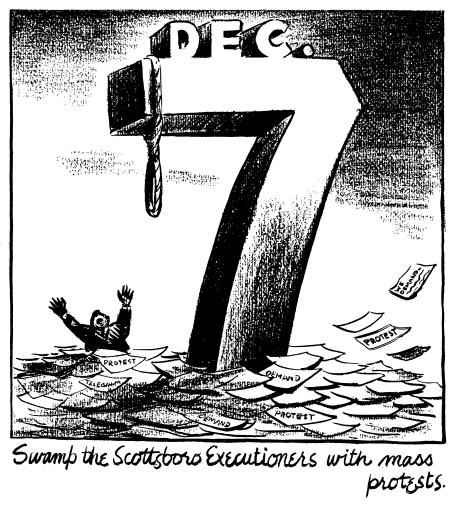

In 1930, nine poor Black men aged 13-21 were arrested and charged in Alabama for the rape of two white women on a freight train. Cases like this were common and, without intervention, the men would probably have been found guilty and hanged if they weren’t lynched first. The Communists spoke to the families of the accused and were allowed to defend the men through their legal defence organisation, the International Labor Defense (ILD). Alongside a courtroom defence, the ILD ran parallel publicity and mass protest campaigns. But Third Period sectarianism didn’t help: when the legendary Clarence Darrow offered to help with the case, the ILD said they’d accept him only if he denounced the NAACP.

But the ILD—the organisation that had attracted thousands of Blacks across the country to its militant work around the Scottsboro case and others—became steadily less militant as the party shifted rightwards. After World War II it was dissolved.

Black workers were a significant part of the US industrial workforce: they made up 9.9 percent of coal miners, 18.9 percent of metal industry workers and 35 percent of longshoremen. It wasn’t until 1935 that rising militancy led US union officials to establish the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which aimed to unionise industrial workers in mass industries. In 1930, there were only 50,000 Black union members in the US. By 1940, there were half a million.

Communists played a crucial role in organising Black workers once the CIO was founded. Three of the first six Black organisers of the CIO-affiliated United Auto Workers had previous experience with the Communist-organised Auto Workers Union. The Communists, in alliance with A. Philip Randolph and various Black liberals, established the National Negro Congress, which played a central role organising Black workers into the CIO and challenging racism in the union movement. But the CP accepted a role as a furtive junior partner. The Stalinist Popular Front meant party members were expected to downplay or hide their membership and tail liberal allies. Over time, the CP abandoned rank-and-file militancy and subordinated its union work to CIO leader John L. Lewis and his growing bureaucracy.

● ● ●

The Communist Party squandered its legacy due to its leaders’ slavish adherence to Stalinism. In their militant period, they cultivated a sectarian and bureaucratic approach, and failed to build a revolutionary workers’ movement with a democratic culture. This helped them carry out a swift bureaucratic shift to the right. During the Popular Front period, they drove their party towards alliances with capitalists and bourgeois politicians, including southern racists, right up to the madness of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact. Once that pact was broken, the party became ultra-patriotic warmongers, even denouncing strikes during the war as pro-Hitler.

After the war, their supposed liberal “allies” turned on them as the Cold War developed. Communists were systematically driven out of the workers’ movement and from liberal organisations like the ACLU and the NAACP. Repression isolated Communists: in the south, the police, white supremacist groups and the broader political establishment went on the offensive against left-wing influence in Black politics. Terrorist acts like lynchings and firebombings, the violent break-up of demonstrations and anti-sedition laws made it difficult for the Communists to print and distribute literature or organise openly.

Some legacy survived in the many activists who passed through the party at that time. Links with the Communists in the 1930s are a common feature in histories of the civil rights and Black power movements. Veterans of the SCU were found in the Louisiana Deacons for Defense and Justice, which defended the students on the Mississippi Freedom Summer voter registration drives of 1964. Rosa Parks took courses at the Highlander Folk School, which was founded by a couple of Communist sympathisers in the 1930s. Hosea Hudson, the sharecropper and steelworker who became a Communist workers’ leader, was active in the Free Angela Davis campaign in the 1970s.

But the severing of the links between the left, the workers’ movement and the working-class Black community shaped the future struggles for black rights. By the end of the 1950s, middle class Christian activists were the hegemonic leaders of the southern civil rights movement, encouraging its early principle of non-violent civil disobedience and a more legalistic approach than the class struggle of the Communist-influenced movement before World War II.

Doctrinaire, sectarian and dutiful to Moscow on the one hand, surprisingly subtle in its relations with oppressed groups such as the Black sharecroppers on the other: the Communist Party in the 1930s was a mass of contradictions. Its work, and the work of thousands of Black workers who joined it, proved the possibility of a Black American revolutionary workers’ movement– an achievement the party threw away in its adherence to the Stalinist distortion of revolutionary politics.