Five things to know about the independence movement in Catalonia

Last year, a group of Global Justice Now activists went to Barcelona to see how movements for food sovereignty, energy democracy and housing rights had created significant infrastructure and fed into the historic win by Barcelona En Comú (Barcelona in Common) in the city council elections the previous year.

Having seen those movements first hand, it’s easier to appreciate why what’s happening in Catalonia isn’t simply an outbreak of fervent nationalism, but something much more interesting for advocates of social justice.

Here are five dynamics of Catalan independence.

1. The Spanish state

Unlike in Portugal, where the fascist dictatorship was overthrown in the Portuguese revolution in 1976, in Spain Francisco Franco’s regime came to a negotiated end after his death in 1975. That means that the new democratic Spain was the result of a compromise between democrats and the alliance of conservatives and fascists that made up Franco’s regime.

Catalonia and other regions such as the Basque Country whose civil rights had been severely repressed (it was basically illegal to speak Catalan or Basque in public) were granted the right to be educated in their language and allowed regional parliaments. Yet at the same time, Spain as a whole was considered “indivisible” and any formal move towards independence outlawed in the constitution.

There was no reform of the police – Franco’s Guardia Civil simply continued, and an official policy of forgetting was put in place in relation to the many thousands of people killed and disappeared by the regime. Not only were there no prosecutions, but neither was there a “truth and reconciliation” process such as the one used when apartheid ended in South Africa.

Franco’s henchmen reconstituted themselves into the new conservative party, the conservative Partido Popular (People’s Party) which has alternated in power with the social democrats ever since, and which is in government now.

2. Independence on left and right

Unlike in Scotland where the Scottish National Party is clearly the dominant party of independence (even if the Greens offer a pro-independence alternative), Catalan pro-independence parties span from centre right to far left. At the last regional elections in 2015, the centre right Democratic Convergence and centre left Republican Left ran on a joint ticket together with some more minor parties. The aim was a one-off attempt to get a clear majority for independence in the Catalan parliament. Although Junts pel Sí (Together for Yes) failed to get a majority, the anti-capitalist independence party, the Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), which ran separately, also won 10 seats. Together they have a majority, and after some hard negotiation agreed a roadmap to independence.

Nationally and in Catalonia the conservatives and social democrats (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) are firmly against independence, while Podemos is against independence but for the right to decide and has been vocally against the repression meted out by police.

One of the main arguments against independence on the Spanish left has been that it is based on separatism for one of Spain’s wealthiest regions which doesn’t want to see its wealth redistributed to poorer areas. But the CUP’s Lluc Salellas argues that although “Spain robs us” was once a more dominant slogan, now the discussion is about democratic and civil rights. He adds that “the CUP has said for a number of years that an independent Catalonia should pay money to poorer parts of Spain in the transition. It doesn’t have to be a short time, it could be 20 or 30 years … We are internationalists and we are in solidarity with workers and the poor in Spain”.

3. Nationalism vs. independence

There is undoubtedly a strand of the Catalan independence movement which looks a lot like any kind of nationalism, downplaying the differences of interest between ordinary people and the elite within Catalonia, while implicitly or explicitly excluding outsiders. For an older generation of workers, many of whom have come from other parts of Spain, Catalan nationalism is a distraction from class inequality. On the other hand, modern Catalan nationalism was born mainly in response to the oppression of Catalans by Spanish fascism, and as such its dynamic is at least a demand for freedom, not for domination over others.

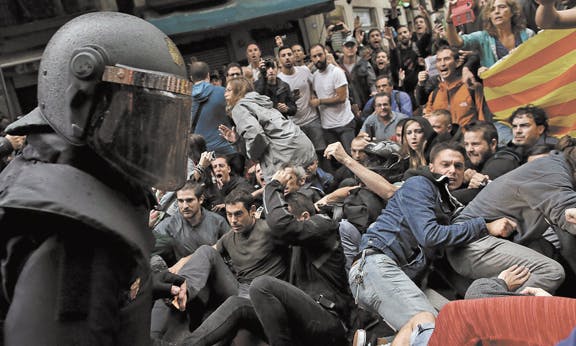

Even though Catalans now have many of those freedoms, casual anti-Catalan sentiment is still evident in much of Spain. One Catalan woman reports an overheard conversation in Madrid on referendum day, as the Spanish police were attacking people: “These Catalan people just need a couple of slaps to learn they have to stay”. The behaviour of police in the videos from the day of the vote suggests not servants of the law following orders, but bully boys chosen precisely for the contempt they already had for the people they were beating and throwing around.

But if a macho Spanish nationalism is the bigger evil here, is the independence movement merely trying to fight fire with fire? Just as in Scotland where radical independence campaigners said “Britain is for the rich, Scotland can be ours”, there seems to be evidence of a new mood in Catalonia whereby independence is a necessary step towards a truly democratic and egalitarian society. Lluc Salellas again:

“The last 15 laws we have passed in the Catalan parliament have been banned by the Spanish state. But these are not independentist laws — many of them are social laws: for example, a law about sanctuary for those fleeing persecution, a law banning energy companies from turning off people’s electricity, and a law for a higher minimum wage.”

Of course, that won’t be everyone’s view, but with popular Committees in Defence of the Referendum having formed and a widely observed general strike against the repression of the movement, the momentum is with the progressive radicals and socialists at the moment. In other words, events around the referendum have pushed independence organising even further away from a nation-building project and towards being a popular democratic revolt.

4. Participatory democracy

Paul Mason writes of his experience in Barcelona on the day of the referendum: “People stood in the rain and talked in small groups – without hand gestures or raised voices – about what to do. This street space … was alive with democratic argument”. He argues that a form of true democratic participation is emerging in Catalonia which extends far beyond the idea of replacing a Spanish parliamentary democracy with a Catalan one.

Of course this emergent participatory democracy hasn’t come out of nowhere. Barcelona is governed by mayor Ada Colau and her Barcelona En Comú coalition, which has made democratic participation in the decisions of the municipal government a key policy. This has happened both online and through regular neighbourhood meetings. This revolution in local government has also started to impact on other municipalities across Catalonia. (Colau has called on Rajoy to resign because of the police violence, and although she cast a blank ballot in the referendum, defends the right of Catalans to vote on independence.)

From the “indignados” movement (called 15M in Spain) which took over public spaces across the whole country in 2011 to other initiatives such as that around a people’s “Constituent Process” across Catalonia, the sense of politics being everyone’s business and something there should be no barriers to involvement in has been building for some time now. That’s one reason that the independence movement has a different character from how it looked a decade ago. In a sense it is part of the revolt against neoliberalism that is happening right across Europe.

5. Catalonia and the European Union

Strangely in Britain, the Daily Express has been among the most vocal in condemning the European Union for not speaking out against the repression during the referendum. Since the Express isn’t known for its principled defence of the civil rights of foreigners, we can only assume it has its own reasons for attacking the EU. But in any case the European Union is not really a single political actor anyway, but a club of states which tend to act out of self-interest. Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy is a key ally of conservative German chancellor Angela Merkel, and other powerful states have their own regional independence sentiment which they don’t want to encourage.

In fact the Belgian prime minister did condemn Rajoy’s repression, and there was condemnation from the European parliament too. But real power in the EU currently lies with states committed to a neoliberal consensus which they are hoping events in Catalonia don’t disrupt.

Yet the EU’s set up in some ways makes Catalonian independence feel more possible, with open borders between many member states and common institutions making sovereignty potentially more fluid. This other dimension of the EU stands in contrast to the realpolitik of the club of states who make up the Union.

The modern Catalan independence movement, then, reflects a struggle between competing versions of a future Europe – either a technocrat’s Europe operating in the interests of finance and the 1%, or an internationalist Europe of democratic self-determination. If it can help constitute the latter, Catalan independence could make a difference to our future too.