The Black Panther Party: from Black power to people’s power

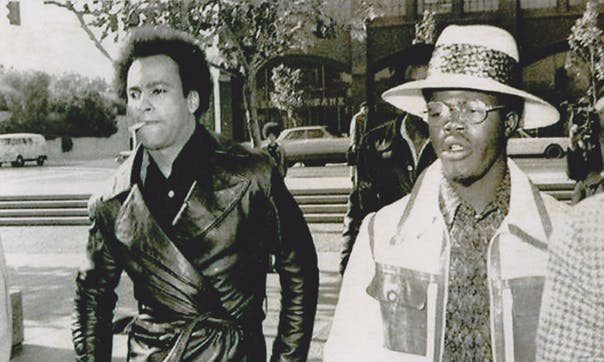

Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in October 1966 in Oakland, California. The Panthers practised militant self-defence against the US government and fought to establish revolutionary socialism through mass organising and community-based programs. At its peak in 1969, the party had a membership of 10,000. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called the Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”. Though the party disintegrated due to a combination of state assassinations and internal splits, it left an indelible impression on US politics. Former Panther Billy X Jennings spoke to members of Socialist Alternative when he visited Australia several years ago. The following is a transcript of the discussion.

----------

Why did you join the Black Panther Party?

I joined because I wanted to do something positive for Black people and I thought it was the best vehicle to do that. After reading their 10-point program, I thought their direction and what they were shooting for in the future was something I wanted to be a part of. Also, they really appealed to young people at that time because they were an organisation with ideas, and it seemed like they were trying to implement their ideas. The older organisation that had been around was entrenched in the establishment already, and the Black Panther Party was outside of that – they were actually talking about revolution. I thought that was something we needed in America because the present situation was killing Black people. It was very oppressive for poor and Black people. So I thought that was the best avenue for me.

What sort of education did you get in the party?

To join our organisation, you had to go through a training process. When you joined, they gave you an outline of what was expected of you. In that outline they had a reading list of about 30 books that you had to know something about. For instance there were two books – Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon, and another was A Dying Colonialism – we had to read books like that, the Red Book [by Mao Tse Tung], books by Che Guevara, books by Fidel Castro – books by revolutionaries who actually won or participated in struggle like Patrice Lumumba.

Other books on the list were the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. Later on as a group we would read What Is To Be Done? by V.I. Lenin. I’m not saying we were practising Marxists, but we knew what it was. We knew what dialectical and historical materialism was by studying it. It was an ongoing process. And every party member had to carry the Red Book with them. If you didn’t have your Red Book on you, that would be like 50 push-ups on the spot because to us the Red Book was transforming a group of Blacks who had never had any discipline – these are young people – into a fighting revolutionary force. And Mao Tse Tung had done that with the same type of people – workers, lumpenproletarians, students and so forth – most of the people in the party were young people. So the Red Book was very crucial to us at the very beginning. We moved on past the Red Book maybe a couple of years later, but it was very essential for us at that time.

We heard that you used to raise money by selling copies of the Red Book to students at Berkeley?

Actually, Huey [Newton] found out that there was a place that sold the books for about 25 cents. We went over there and bought some and sold them on for a dollar. That was a way for us to raise money until we were able to publish our newspaper. But we carried the Red Book, we quoted from the Red Book – we would even tear pages out of it and nail them to our walls because what they were saying was so profound.

What were your roles in the party?

As a student – I was 17 when I first joined so I was still going to college – one of the roles I played was, in 1969 we started a free breakfast for schoolchildren program. I, being a student, had classes from 9 in the morning to 12 noon and on Tuesdays and Thursdays they went to about 1 o’clock or something like that. That gave me time to participate in the breakfast program. We started at about 6:30 and went to 8 o’clock. That gave me enough time to go feed kids in the morning and make it to my first class. That was my first duty.

I also would sell the Black Panther Party newspaper. We really believed in propaganda and educating people. That was the way we were trying to reach people. The newspaper was a tool to educate and organise people on what the Black Panther Party was really about. It had our 10-point program in it; it had an international section, which carried news about other struggles and revolutionary [events]. It had articles written by party members from all over the country. So even if you were from New Jersey or Kansas City you would see some articles from there.

The paper became a source to raise money. Every party member would take out papers every day – like a hundred – and sell them. You had your profit from that. The organisation would keep 15c and you would keep a dime [10 cents] because we had to have some way of building our organisation and we had to have a way to support our workers. We were, you know, 18, 19, 20 – a lot of party members were living at home and parents are still trying to rule you in some sort of manner because you’re in their house. Party members were getting kicked out of their houses for not following the rules, so we needed houses for party members to live. Through the newspaper, even though we only kept a dime out of every sale, if you sold 100 papers you’d have $10. You could live off that in 1968.

The party newspaper was necessary because it educated people in the community, it represented what we thought and what we believed, and it came directly from us. It also helped us, the party members, come up. You have to realise that we came from nowhere. We had no offices. The offices we got we got with nickels [5 cents] and dimes. I mean everyone chipped in money raised from the newspapers. After a period of time we went from getting a dime to maybe a nickel. So we got 50 guys kicking in nickels per issue and they’re selling something like 5000 papers a week. That would be enough for us to get an office. That would be enough so that when people went out to sell papers and do community work, they would come back and we’d have food for them. We built the organisation from ground up, from one office to 51 offices. And the infrastructure was started from selling that newspaper.

As I developed more, the organisation promoted me to a position called “officer of the day”. Officer of the day is the person who runs the office. He delegates authority under the captain, who sort of runs everything. I would open up the office at 9 o’clock in the morning. I’d issue the papers to people, tell them “You’re going to this area and you’re going to that area ...” My job was also security. I always had a gun – because at that time the police were always raiding our offices and stuff like that. I told myself, “I’m not going to be a victim. If I’m going to get hurt, so are you”.

I was a dedicated party member. Then I was promoted and moved to central headquarters. When Huey Newton got out of jail in 1970, the organisation’s Central Committee made it my job to be his aide. That would mean going to court with Huey, because even though he was let out on appeal, he still had to go to court over the murder of a police officer. I worked with Huey for maybe about a year, and then in 1972 the organisation decided to run Bobby Seale for mayor of Oakland. It was my job as a section leader to run Bobby’s main campaign office. We had six other offices in Oakland, but mine was the main one. From there I worked on the campaign. Matter of fact, we got to the final run-offs [between the top vote winners in the first round of the election]. We ran against eight other candidates. One was a sitting member of City Council, another was the mayor there and so forth. But our organisational skills outdone them all. Even though we didn’t win, it set the stage for Oakland to change. That was the first time that Blacks had any chance of achieving political power in Oakland.

Because of what happened with Bobby Seale’s campaign, the next election there were three or four Blacks who actually won seats with the help of the Black Panther Party. After the election, I was moved to the Oakland Community School. It used to be a Catholic school, and we bought the whole building, which took up a whole block. It had 15 or 20 classrooms in it. It was my job to raise funds for that. So I would go to [tennis player] Arthur Ashe [musician], John Lee Hooker or whoever came to the Bay Area [encompassing San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose], try to get an appointment with them, talk to them, try to bring them to the school. I did that till I left the Black Panther Party in 1974.

What kind of activity was expected of a party member in a typical week?

First off, you had to attend political education class. We had two classes we had to attend. The local one at the office you worked at. And if you lived in the Bay Area, the national office had a national political education class that was run by Bobby Seale, Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver or someone in the leadership. Plus you had to read two hours a day on your own.

Every Panther was delegated a section – a certain geographical area where you would sell papers. You might go downtown to sell papers. But in the evening you would go back to your section – that was so everyone would get to know who you were, you would become a fixture in that area. If people had problems, they would know the Panthers who would come around week to week selling papers. So there was work in the community. We went door to door, we also attended community meetings.

Working with student organisations was another thing because during that time there were Black Student Unions (campus organisations). The BSUs worked to make the school serve them, by teaching classes they could use in the real world. So we would work with Black Student Unions, on college campuses, high school campuses, and we would gain many recruits from people who liked what we said and wanted to work on our social programs.

You might be scheduled to the breakfast program three days out of five per week, and then as the party began to grow, we began to establish other social programs like Liberation School, because they weren’t teaching Black history in high schools and many colleges yet. We had classes for the community given by party members talking about Black history, the Black situation, how Blacks dealt with situations in the 1940s and 50s.

Working on the social programs probably took up most of our time, working in the community, going door to door and dealing with issues like legal aid. Due to the racist nature of America, Black people were always being arrested, a lot of the time for no reason at all. So we had a legal aid department. Someone would come in and say, “Hey my son got busted; he’s down in the county jail. What can you do?” We would give them a method of how to deal with it.

When I was a Panther, I was still going to school. And one of the classes I took was criminology. In school they have like an intern program – in America they call it “work-study”. I ended up working in the Public Defender’s office, so I knew a little about law and stuff like that – how to get a public defender lawyer. So mostly it was aiding people in the community, dealing with situations, and working on survival programs.

What, in your opinion, was the party’s greatest achievement?

The greatest achievement was the coming together, being a torch, a light. Because it was pretty dark in America. The Black Panther Party carved a pathway. We set the table for the actions for the future, because we dealt with issues that hadn’t been dealt with before, like male chauvinism. What organisation actually dealt with male chauvinism? Organisations at the time had women walking two or three feet behind.

Another great achievement was that our programs were successful. They became the staple of American society. Kids in every state, in every county, can have a free breakfast now. Who did that? The Black Panther Party. The Black Panther Party started a free bus into prison program. I don’t know any major church that doesn’t send buses into prisons now because so many people from their congregation have people in jail. The senior escort service was another – helping senior citizens avoid being victims of crime. There wasn’t any direct deposit back then, and the criminals knew that. Once you got the cheques cashed at the bank you were lucky to make it back to the seniors’ home. So we would escort them.

So there was a lot that the Black Panther Party did in terms of directly helping people. Sickle cell anaemia education – we did a lot to help identify that disease. These were things that the party did not just for Black people, but for the whole of society. Even though we were a Black organisation and our main focus was Black people, we accepted humanity. We dealt with Black, Chicanos, whites, Asians. We believed you deserve a better life; you deserve the best that society can offer. We stopped saying “Black power to Black people” and starting saying “All power to all people”.

We stopped classifying everything by race and started dealing with the class struggle. We started educating people to the fact that we are all victims; we are all in this boat together. We’re going to row this boat in the same direction because we have a common enemy, we have a common goal, and the same people who are oppressing you in the Asian community, in the white community, are oppressing us in the Black community as well as the Latino community. We were able to draw from the class struggle and have coalitions with a lot of organisations, and we dealt with a lot of issues together – as a unit.

The government didn’t like that. They like to use racism, which is a by-product of capitalism, to divide people. You know they did that to workers throughout American history.

How do you think that the Black Panther Party changed politics in the United States?

We were like a direct action organisation. We were grassroots, we represented the people. We changed the everyday politics of bullshit to dealing with issues. What are you going to do about feeding kids? What are you going to do about police brutality in our community? Direct action. That changed the way business was done. That changed politics; we developed in-your-face politics. The Panthers did things.

We ran Bobby Seale for mayor, but before we did that we put an initiative on the ballot called “Community control of police”. Never before had people been given the choice of what sort of police department they wanted. We were saying that the police had to live in the community that they represent. No longer would you have white racists living in white communities coming down to a Black community and occupying it like foreign troops. You would have to have officers that lived in your community.

With the election of different Black officials, they were more focused on solving people’s problems. Out of that came different party members who held different political positions in America. Barbara Lee for example, she was a student under me, and she was co-head of the [congressional] Black Caucus for all America.

The BPP were the torch in the dark, lighting the way.

----------

First published in Socialist Alternative magazine.