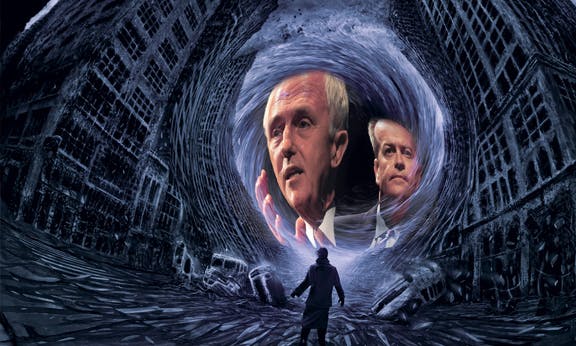

Staring into the void of Australian politics

Five prime ministers in five years. None serving out a full term. Each more right wing than the last. First term governments defeated in Victoria (for the first time in 60 years) and Queensland. Official politics in Australia has been in a state of turmoil.

Malcolm Turnbull was supposed to end it. Made desperate by falling polls, the parliamentary Liberal Party, a majority of which despised his apparent adherence to post-mediaeval views about women and homosexuality, decided he was worth a try. They were backed by corporate screeches that Abbott had not done enough to wind back workers’ rights, cut taxes on the rich and slash spending that benefits the rest of us.

But under Turnbull the Tank Engine, the Liberal train has continued rolling down the same tracks.

While business may be pleased that the Coalition is finally taking action in the union-bashing spirit of Abbott’s royal commission by going to an election over industrial relations, Turnbull’s increasing unpopularity has hampered the government. And corporate Australia is not happy that the promised pro-business “reform agenda” has again been stalled. So one of its Fat Controllers, the director of the oldest conservative think-tank, the Institute of Public Affairs, has complained:

“If Turnbull raises taxes and doesn’t cut government spending, one of the reasons for him being leader disappears. Turnbull presented himself as a reformer and an economic liberal. So far, precious little of that has been seen.”

Moving right

Mainstream Australian politics has been ratcheting to the right for a long time under both Coalition and Labor governments.

Social welfare entitlements are pared back year after year. More and more of the health system is being privatised. Public education is being run down while billions of taxpayer dollars are handed to private schools. The unemployed are being subjected to an ever more draconian benefits system. Taxes on corporations and the rich have declined.

In terms of neoliberal economic policy, racist policies towards Aborigines, refugees and Muslims, and foreign policy mainly shaped by the US alliance, it’s becoming harder to slide a piece of paper, let alone cardboard or a decent chunk of four by two timber, between the approaches of the ALP and the Liberals.Civil rights have been eroded. On the pretext of making us safe – particularly from terrorism, sexual violence and drug use – new crimes (including thought crimes) have been created, penalties increased and police powers expanded. Police and other agencies can detain people without charging them for longer and without access to a lawyer. We are subjected to sniffer dogs on the streets and in venues. Lockout laws are a new prohibition.

“Welfare management”, which started with Aborigines, dictates what social security recipients can spend their incomes on.

Punitive testing has been part of the roll-back of more enlightened, child-centred approaches to education, which emerged from the climate of greater struggle from below between the mid-1960s and the 1970s. Structures modelled on private corporations have eliminated the very limited democratisation of universities that dates back to the same era.

The shift from three- to four-year parliamentary terms in all states, further restricting our already limited democracy, was completed this year in Queensland. Both sides of mainstream politics backed the change. Expressing the common sense of CEOs, journalist Jim Middleton has noted:

“In Australia there is even less time than elsewhere for a new government to establish itself and start engaging in necessary, if unpopular reform, before setting itself up for the task of re-election … Business has long pushed for longer parliamentary terms.”

Nationalism and racism have become ever more important in securing popular support. Governments and the mass media promote pride in national sportspeople and teams, concern about Australia’s position on various economic and educational league tables and the militarist “ANZAC spirit”.

Islamophobia in particular has become the main justification not only for Australian participation in military adventures intended to make the world safe for the profits of corporations based in the USA (and its allies) but also for vast increases in spending on the armed forces, policing and spying.

Bipartisanship on most of this has helped ensure that there has been only episodic mass resistance, despite the desire of most of us for improved public services.

The great divide

For thirty years, the proportion of people in Australia who prefer more government spending over tax cuts has tended to rise. Today it is 55 percent, according to a March ANU poll. A large majority think that “upper income people” pay too little tax, and very large majorities believe that international and large Australian companies don’t pay enough. More than three-quarters want the government to spend more on education, health and aged care.

The Scanlon Foundation has found that that more than 70 percent of those polled regard the gap between rich and poor in Australia as too wide. In the latest poll, last year, the proportion was a record 78 percent.

So the gap between what the ALP and Coalition do and these widespread attitudes has broadened. The parties have moved to the right while most people have moved to the left.

Decades of neoliberal policies and attempts to distract attention from them, under Labor and the conservatives, and the jolt of the global financial crisis followed by years of slow growth have intensified problems faced by workers and the system’s scapegoats. And governments have made matters worse.

Consequently, the core support for the main parties has been in decline for a long time, and political instability has increased. No wonder the electoral mood can swing dramatically. Voters kick out one lot in the hope that things will get better, but they don’t, so they look for something different again.

Between the federal elections in 1946 and 1975, the share of the ALP and Coalition parties in first preference votes never sank below 89 percent. Since 1996 it has never been above that level, and there has been a more pronounced downward trend since 1983 to reach the lowest point ever, 79 percent, in the 2013 elections.

The Coalition has faced right wing populist challenges: Pauline Hanson in the 1990s, Clive Palmer and Bob Katter in the 2010s. The element of their rhetoric that highlighted problems ordinary people face and governments have failed to address also had some appeal to disaffected Labor voters.

But Labor, with its organic links to the working class through the unions, has suffered more than the conservatives. In terms of neoliberal economic policy, racist policies towards Aborigines, refugees and Muslims, and foreign policy mainly shaped by the US alliance, it’s becoming harder to slide a piece of paper, let alone cardboard or a decent chunk of four by two timber, between the approaches of the ALP and the Liberals. On the issue of paid parental leave, Tony Abbott initially outflanked Labor to the left in generosity to workers.

At the same time, local ALP branches have been hollowed out. Lacking the personnel itself, the party has increasingly relied on union officials and union activists to engage in face-to-face or phone-to-phone electoral campaigning.

The priority most top union officers place on getting Labor elected has been a substitute for and drain on resources for a more effective strategy to rebuild their declining memberships. That would involve building their organisations by leading industrial campaigns in defence of their members’ pay, conditions and access to public services like education and health care.

Much of the trend away from Labor has been due to the rise of the Greens. But with their success, they have become more like the other parties: moderating their positions in order to win more parliamentary seats.

Power in the darkness

Australia’s relatively smooth path through the global financial crisis, largely thanks to mining exports to China and a booming residential property market, has meant that there has been less political desperation than in Europe and the United States.

There, the failure of mainstream parties and politicians to address people’s mounting financial problems has fuelled political polarisation. On one side, there is the rise of the far and fascist right in a series of European countries, including Austria, France, Germany, Greece and Hungary. In the USA, the popularity of Donald Trump’s right wing populism has the same cause.

On the other side of the political spectrum, left wing challenges have emerged, sympathetic to workers’ interests and arguing for social solidarity: Jeremy Corbyn’s rise to the leadership of the British Labour Party, Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in the USA and Syriza, before it took government in Greece. Even more significantly, there has been mass resistance to neoliberalism on the streets and through strike action in Europe.

There is no equivalent revival of a moderate social democratic force in Australia, notwithstanding Shorten’s half steps to the left on negative gearing and a bank royal commission. These hardly compare with Corbyn’s and Sanders’ proposals to break up big banks and for large-scale public spending.

Nor has Australia experienced a major right wing mobilisation, although the scale of Reclaim Australia’s early racist demonstrations and the impetus they gave to hardened fascists indicates that, unless they are resisted at this early stage, they could find a much wider audience during a serious economic downturn.

And the labour movement remains almost totally inert.

But there is very widespread discontent. This is apparent not only in opinion polls. The shock of the Abbott government’s aggression prompted the “March in March” protests and then large demonstrations against the savage cuts announced in the 2014 budget. Large student rallies against the deregulation of university fees continued into 2015. These actions were the major factor in securing the defeat of many budget measures in the Senate.

There have been other bright flashes in the gloom. Workers at the huge Woolworth warehouse in Laverton, Melbourne, took illegal strike action last August and briefly broke the pattern of industrial passivity. In February, workers, supported by solidarity activists, prevented the removal of a refugee baby from the Children’s Hospital in Brisbane, back to the concentration camp on Nauru. Counter-protests have successfully confronted Islamophobic rallies across the country. These flashes point to the potential for change.

For the capitalist class, democracy, elections, changes of government (unless the government is deemed bad for business) are, at best, irritating hassles. As far as they are concerned, the less democracy the better.

It’s different for those of us who have to make a living by selling our capacity to work and experiencing oppression. To defend our interests we need to build our power and extend democracy, particularly where we spend so much of our lives and it has never existed: in our workplaces.