The role of Queensland Native Mounted Police in genocide

The premeditated use of murderous violence against Indigenous people by agents of Australia’s early colonial order is often glossed over. For many commentators and politicians, it is too much to admit any element of malice.

Take Malcolm Turnbull describing the adorning of statues of Captain Cook and Lachlan Macquarie with the slogan “No pride in genocide” as equivalent to Stalin’s systematic attempts to “obliterate” history that did not fit his totalitarian rule.

Despite these attempts by the Australian state to deny history, historians such as Jonathan Richards and Bill Rosser have done much to unearth the genocidal intent of some of the early pioneers of policing. Their books, The Secret War and Up Rode the Troopers, examine one of the more chilling examples of brutality: the Native Mounted Police, which operated in Queensland from 1848 until the early 20th century.

In its early years, the Native Police was overseen by New South Wales, even as the edges of settlement pushed up into the area that is now southern Queensland. In forming the first corps of the force, NSW governor Charles Augustus Fitzroy explained clearly its purpose:

“Circumstances having been recently brought under the governor’s notice, in respect of certain collisions which have taken place, in parts beyond the Settled Districts, between the white inhabitants and the Aborigines, which appear to him to require that immediate steps should be taken for their repression.”

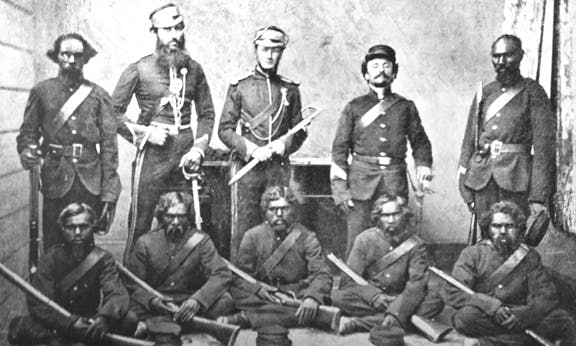

The Native Police was organised similarly to other colonial forces. The bulk of the force consisted of Indigenous men forcibly conscripted and armed by the state, who would typically patrol on horseback.

From the 1870s, the Queensland authorities offered Aboriginal prisoners remission of their sentences in return for service. Although it was under the command of the commissioner of police in Brisbane from 1864, the Native Police officers were always called “troopers”. No trooper ever advanced beyond the rank of constable.

Indigenous men were recruited as part of the authorities’ divide and rule strategy. They intended to reward loyal tribes and exterminate oppositional ones. The skill of Aboriginal troopers in tracking and foraging was much appreciated by the authorities. But recruitment proved difficult. One anecdote, passed down through the generations, notes Aboriginal men kidnapped by the Native Police deserting and walking 550 kilometres to their homes.

The Native Police patrolled both the frontier of the colony and the vast swathes of territory occupied by Indigenous people. Neither Britain nor its colonies ever formally declared war on the Aboriginal people; ostensibly, they were British subjects. But Indigenous people confronted settlers as hostile invaders.

So the Native Police functioned outside of the law and the “civilisation” of which it was the armed vanguard. This produced a Kafkaesque quality in the force. Even though its activities were openly understood by the highest authorities of the state, and by squatters who called for its assistance, in official police reports the term “dispersed” is always used rather than “killed” or “shot”.

Using Aboriginal troopers also prevented reports emerging in the press about massacres – Aboriginal people were not considered reliable witnesses to murder, and were not sufficiently literate in English to leave written testimony. On top of this, the rules of the Native Police stipulated that troopers were not to have contact with whites outside of the force. Thanks to these efforts, the exact scale of the killing is unlikely ever to be accurately calculated.

Testimony to Aboriginal resistance, it was official policy that officers ride at the rear of the patrol lest they be shot in the back by their troopers. Of these officers, one infamous murderer stands out: Frederick Wheeler.

Wheeler began his career in the Native Mounted Police prior to the separation of Queensland from NSW, first as lieutenant and then as inspector. Wheeler was deployed to the northern Brisbane suburb of Sandgate early in his career, where a barracks erected at the current site of Sacred Heart Primary School was located between 1858 and 1865. From Sandgate, his patrols ranged far afield.

In one incident, three burning bodies of Aboriginal men were left on a farmer’s property in Fassifern, near Ipswich. This led to an enquiry by the Queensland Legislative Assembly in 1861. The men had been chased down by Wheeler and his troopers, shot through the head and their bodies set alight to hide responsibility.

It emerged during Wheeler’s testimony that the three killed at Fassifern were survivors of a larger massacre at Dugandan, south-west of Brisbane, near Beaudesert. Under questioning from committee chair Robert Ramsay McKenzie, Wheeler testified in relation to this incident:

Q: What were [sic] the nature of those orders [given by Wheeler to his troopers]?

A: I told them to surround that camp of Telemon [station] Blacks, and to disperse them.

Q: What do you mean by dispersing?

A: Firing at them.

Q: What are the general orders of your commandant?

A: It is a general order that, whenever there are large assemblages of Blacks, it is the duty of an officer to disperse them. There are no general orders for these cases; officers must make sure that proper discretion is exercised.

Q: Don’t you consider this a very loose way of proceeding – surrounding Blacks’ camps, and shooting innocent gins [Aboriginal women]?

A: There is no other way.

Despite the admission by Wheeler that he had ordered the slaughter of an entire tribe, the committee found that the force was operating precisely as intended. Wheeler continued his career in the force and was involved in more massacres. In 1862, he “dispersed” Aboriginal people at Cleveland and Bulimba, before being sent north.

Asked if the Native Police in Sandgate had helped in “civilising” the local Aboriginal population, Wheeler said, “That is a question I am not prepared to answer, I know so little of the Blacks. They run before me – I never see them”.

After a nearly 20-year career, in 1876 Wheeler was charged with murder for publicly flaying an Aboriginal man to death in Clermont. He fled and died in Java in 1882.

Wheeler was the most horrific and murderous manifestation of the Native Police, but not the only one to unleash brutality. John O’Connell Bligh, grandson of governor Bligh, served as a lieutenant in the Maryborough region from 1854 until 1861, when he was promoted to commandant in charge of the entire force. In 1860, Bligh and his troopers, possibly intoxicated, attacked a group of Aboriginal people camping near a store. A letter from a witness described to the Moreton Bay Courier:

“Mr Bligh, with a party of police, rode into town … charged a camp near Mr Melville’s, drove the poor creatures from it – some through the town, some into the river – and commenced butchering them forthwith.”

Some were shot down in the street or while attempting to escape through the river. At least one man was taken away and executed. While some whites were outraged, many inhabitants of Maryborough welcomed the ethnic cleansing. Money was raised to present Bligh with an ornate sword “for his services in suppressing the outrages of the Blacks”.

As commandant, Bligh oversaw punitive expeditions against the Aboriginal population around Springsure after the Cullin-La-Ringo massacre in October 1861. The local Gayiri people attacked a newly established station with more than 10,000 head of sheep. In response, about 300 people from the tribe were slaughtered by vigilantes and the Native Police.

Officers often graduated to distinguished positions within the Queensland Police Force. Frederic Urquhart, a sub-inspector of the Native Police, led an assault against the Kalkatunga (Kalkadoon) people near Mount Isa in 1884. After being speared in an ambush and wounded again during the final massacre of the Kalkatunga, Urquhart unfortunately survived to become commissioner of police in Brisbane.

The Queensland Police Service official history notes that Urquhart was pivotal in the baton charge against trade unionists on “Black Friday” during the Brisbane general strike of 1912, and turned a blind eye to the right wing paramilitaries engaged in the Red Flag Riots of 1919. Clearly, being party to the mass killing of Aboriginal people was no barrier to his promotion to senior state posts.

The Native Mounted Police were vital for expanding the frontier of colonisation. The 1964 Centenary History of the Queensland Police Force describes the Native Police as fighting a “sporadic frontier war … Native Police camps were established in strategic points throughout the colony”. The relative weight of the Native Police compared to the “ordinary” (European) police is well illustrated by the size of each force when Queensland first established its own police in 1864: 137 individuals served with the Native Police and 150 in the regulars.

Despite the deliberate vagueness of police reports, it is clear that thousands of Aboriginal people were murdered by the Native Police.