Backlash after Monash University slashes arts funding

The trouble at Monash began at 9am on the first morning of semester. New students enrolled in the popular first-year Introduction to International Relations unit arrived for class, only to find themselves in a silent and abandoned lecture theatre.

To deal with overcrowded lectures, the administration had taken an innovative new approach to teaching: replacing the lecture with a streamed video to save on hiring academics. And in a pioneering budgetary experiment, it also decided not to pay anyone to set up the room.

“My unit had a streamed-in second lecture theatre with no staff or setup”, one student reported online. “I was told [it was] because they couldn’t afford someone to check in. So people just sat there waiting. [We] will see what happens next week.”

The situation became clear the following week. The university had made significant cuts to the arts faculty, the details of which it tried to keep secret from staff and students. But the extent of the cuts was such that they couldn’t be kept under wraps for long.

Tutorials were so overcrowded that students were sitting on the floor. Some students were told that their tutors couldn’t provide feedback on long essays. Others were told that their tutors had been sacked.

The National Tertiary Education Union called a meeting, attended by around 30 academics from the arts faculty and 10 students. Here, details of the cuts emerged.

Taking the axe to the arts

Like many universities, Monash is highly secretive about its employment and budgeting practices. Its annual reports don’t reveal how many staff are “sessional” (short term casuals) or what they’re employed to do, which allows the administration to hide the fine points of the attacks.

But there are some things we know.

Monash dean of arts Sharon Pickering conceded in an email that the university is “moving away from the practice of overspending sessional budgets”. Strict limits have been imposed on how much can be spent on teaching.

This means job losses and reduced hours for those who keep their jobs. According to employees in the School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, sessional staff with PhDs will no longer be hired; some have already been sacked. The maximum tutorial size has been increased to 30.

Tutors will not be paid for time spent on student consultations: “consultation” must occur in the two or three minutes before and after a tutorial. Nor will they be paid to mark work. In at least one unit, assignments of 2,500 words will be marked, but no feedback will be given to students, so they won’t find out why they failed or passed.

Many courses are shifting assessment toward online quizzes put together by “education designers”. (Defending the cuts, Pickering boasted of having hired four of these “designers”.)

Smaller tutorials focused on detailed discussions are being replaced with a model called a “lectorial”. In the lectorial, dozens or hundreds of students are gathered around large tables while a single staff member, playing the role of an Oprah-like talk show host, walks from table to table interacting with a tiny fraction of the student body. At other times, students undertake group work, never interacting with teaching staff. They then go home to watch online video lectures and perform the online quizzes.

It sounds rather old fashioned. Huge classes instead of intimate discussions. Understaffed faculties with underpaid teachers. Standardised tests designed by non-specialists in place of personal interaction with teachers. Each innovation means teaching staff can be sacked or given reduced hours.

Each also has a buzzword associated with it. “Active learning” – unlike the detested, old fashioned “sage-on-a-stage” model – is called best educational practice. This is how Monash justifies getting first-year students to pay thousands of dollars to have group discussions with each other rather than with a teacher.

The “flipped classroom” means turning the stuffy old model inside out: you do your lectures at home and your homework in class. It is a marketing term for making students pay to watch online videos and then come and do tests under supervision.

Prior to gutting its sessional teaching budget, Monash spent $240 million erecting an enormous “Teaching and Learning” building designed around these principles, with almost no small tutorial rooms, and enormous halls designed for dozens of students grouped around large tables, patrolled by a single underpaid sessional teacher.

Pickering boasts of increasing class sizes, “matching class size to the world-leading infrastructure and active learning teaching environment that our students are now able to access”.

One internal Monash document hopes that its bachelor of arts degree will soon “shift away from didactic, lecture-based delivery” and scrap tutorials entirely. One can only imagine the savings that could be made if lecturers and tutors were a thing of the past: a degree made up entirely of “active learning” through streaming videos and online quizzes, with money once spent on wages now freed up for marketing and executive salaries.

Campaigning begins

When we heard about the cuts, socialist students at Monash immediately organised against them. We had to draw in whatever allies we could to put a campaign together.

Because so much of the information about the cuts was secret, we had to do our own research, while alerting students to the reason for the appalling learning conditions. We set up an anonymous online survey and plastered the campus with posters asking, “Is Your Course Being Cut?”

Within days, the survey had received hundreds of responses, confirming the worst rumours. “I can hardly see the tutor”, one student wrote about the size of their tutorial. “My lecturer told me that assignments over 2,500 words could no longer have written feedback due to time constraints and budget cuts”, wrote another. “I want to do honours next year – how am I supposed to improve without this feedback?”

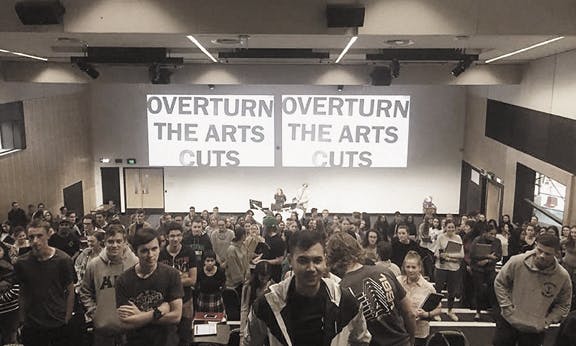

In every tutorial and lecture, we announced the cuts. We organised in-class group photos of students registering their opposition to the attacks on both our own education and the conditions of staff.

This was the best confirmation that the cuts are real, and deep, and that students oppose them overwhelmingly. Hundreds of students joined in. Teaching staff would often explain their experiences of the attacks on their conditions. If you’re a Monash student in the arts faculty, we’d recommend you ask your tutor how the cuts have affected them. You’re likely to hear a horror story.

Having confirmed the widespread resentment of the cuts and the university’s secrecy, we called an open meeting for students and staff. At the time of writing, that meeting has not yet happened: hopefully it will be a forum to expand the campaign.

We sent the dean – by email and by meme, in case she missed the email – a set of demands on behalf of the campaign, which had taken root across the campus: practically every arts lecture and tutorial has become a mini-protest, and creatively placed posters are everywhere.

Under immense on-campus pressure, the dean finally issued a statement to staff, confirming the attacks on “overspending” and promoting “active learning”. But she refused to give detailed figures and brazenly denied the most clearly felt effects of the cuts. This was a small victory: after weeks denying everything, management was forced to confirm that the cuts have happened. Now we have to overturn them.

We aren’t fighting just against the cuts: we’re also fighting against the secrecy of the university and its claim that students love the new model of teacherless courses. We’re demanding that the university open its books so we can see what it’s spending on sessional staff and how that compares to previous years.

And we’re demanding decent class sizes – no more than 20 in tutorials – with feedback on assessments and teachers in all classrooms, rather than online videos. Those demands are just the beginning. The rot runs deep at Monash; many courses beyond the arts faculty are already hollowed out.

Students and staff have made it clear that we aren’t buying the PR gimmicks and secrecy of the university. We are organising students and staff in loud and public opposition, so the university can’t quietly sneak attacks through with a private “consultation” or two on the side.

Fashionable innovations resulting in cuts to jobs and conditions will be coming soon to a campus near you, unless students and staff unite in active opposition.