Building the foundation of today’s Indigenous resistance

The modern movement for Indigenous civil rights and land rights began in Australia in the 1920s and 1930s with the establishment of three key Aboriginal political organisations: the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association, the Australian Aborigines’ League and the Aborigines Progressive Association. These organisations laid the foundations for what would become an independent Aboriginal rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s, and which continues today.

The Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association was established by trade unionist Fred Maynard in 1924. Maynard, who was a member of the Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia, became politicised in the early 1920s working on the wharves, along with other Aboriginal unionists such as Tom Lacey and Sid Ridgeway.

At a time when the White Australia Policy was in force and Indigenous people were forcibly confined to reserves, Aboriginal dock workers such as Maynard, Lacey and Ridgeway engaged with African-American seamen about the struggle for black rights. Inspired by the international black movement and the politics and activism of Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Dubois, as well as the works of Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, Maynard, Lacey and other activists established the association to fight for Indigenous rights in Australia.

Campaigning against the hated NSW Aborigines Protection Board and its control of Aboriginal lives, the Progressive Association called for its abolition and demanded that Indigenous affairs be managed by Indigenous people. It also demanded equal citizenship rights for Aboriginal people, the protection of Aboriginal cultural identity, an end to the removal of Aboriginal children from their families, for Aboriginal children to have free entry to public schools and for land rights in the form of inalienable grants of farming land within traditional country.

Not only did the association try to improve the conditions of Indigenous people, but its members also set a precedent for Aboriginal protest groups: holding street rallies and public protests, organising petitions and writing opinion pieces about Aboriginal self-determination, the mistreatment of Aboriginal children and the failings of the Protection Board.

At the association’s founding conference in April 1925, which was attended by more than 200 Aboriginal people, Maynard said their aim was “spiritual, political, industrial and social … We want to work out our own destiny. Our people have not had the courage to stand together in the past, but now we are united, and are determined to work for the preservation for all of those interests, which are near and dear to us.” Maynard’s impassioned speech about Aboriginal self-determination, along with speeches from other participants, made front-page news, bringing the Progressive Association’s agenda to the public stage.

Over the next two years, the association organised three more conferences, in Kempsey, Grafton and Lismore, and launched a public campaign to expose the horrors of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board. The association’s public agitation for Aboriginal rights and its defiance of the Protection Board resulted in Maynard and other activists coming under police and government scrutiny. Maynard and other members of the association were banned from entering Aboriginal communities on the missions and reserves under control of the Protection Board, and they faced a smear campaign by the capitalist press and intimidation by police, who threatened to jail members and remove their children.

After two years, the first Aboriginal political organisation in the country was forced to end its public activism in 1927. Many of its members, however, continued their activism in a less public manner. At its height, the Progressive Association had more than 600 members.

In 1933, six years after the public demise of the Progressive Association, William Cooper, at the age of 72, founded what would become the Australian Aborigines’ League in Melbourne. A Yorta Yorta man and retired shearer, Cooper had spent the 1920s and early 1930s lobbying on behalf of Aboriginal communities in northern Victoria and western NSW that had been refused government aid. Not formally constituted as the Australian Aborigines’ League until 1936, the organisation included Margaret Tucker, Eric Onus, Anna Morgan, Shadrach James and Douglas Nicholls as key activists working alongside Cooper.

The league’s constitution restricted full membership to Aboriginal people, reflecting the belief of Cooper and other founding members that the organisation should be a voice for the Aboriginal people, who needed to lead their own struggle. Like the Progressive Association before it, the Aborigines’ League accused the Protection Boards run by state governments and their agencies of ignoring the welfare of the people under their control, while destroying Aboriginal communities and cultures.

A year after the official founding of the Aborigines’ League in Victoria, in 1937 the Aborigines Progressive Association was founded in NSW by activist Bill Ferguson. A trade unionist of more than 40 years and a member of the Australian Labor Party, Ferguson had grown up in the period of the great strikes of the 1890s. At 14, he became a shearer and joined the Australian Workers’ Union, for which he later became an organiser.

In 1936, the NSW parliament amended the Aborigines Protection Act (1909), extending the power of the Aborigines Protection Board and extinguishing many basic human rights of Aboriginal people, including the right to freedom of movement, the right to choose where to live and who they could live with, the right to raise their own children, to sell their own labour and spend their own earnings, and the right to choose their own medical treatment and to appeal against an unjust decision of an official.

As a unionist and organiser, Ferguson recognised it was important for the Aboriginal community to resist and fight back in an organised way. Along with Pearl Gibbs, Jack Kinchela and Jack Patten, Ferguson founded the Progressive Association on 27 June 1937 in Dubbo. Like its predecessor, the association called for the abolition of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board, full citizenship rights and Aboriginal representation in parliament.

Ferguson was elected secretary and Jack Patten took the role of president. Like Ferguson, Patten was a well-known Aboriginal activist. After being elected president, he spent five weeks visiting reserves and missions to collect affidavits from Aborigines about their living conditions. The evidence was presented to the NSW Legislative Assembly’s select committee on the administration of the Protection Board. At the committee hearing, Ferguson made it clear that the Progressive Association wanted the board abolished.

“It is not functioning in the best interest of the Aboriginal people”, he said, noting that mission managers and reserve protectors not only had power “greater than any other public servant in Australia” but also greater than the king of England. Even the king did not have “power under the British law to try a man or a number of men and women, find them guilty and sentence them without giving them fair and open trial and without producing evidence to convict”.

On 12 November 1937, Ferguson was the guest speaker at a Melbourne public meeting called by William Cooper. As reported on the front page of the Melbourne Argus newspaper the next day, Ferguson said of life on the Aboriginal reserves in NSW: “It would be better for the authorities to turn a machine gun on us”.

Cooper and the Aborigines’ League agreed to give their full support to the Progressive Association, which planned to protest the following year in Sydney on 26 January, when celebrations were scheduled to mark 150 years of European colonisation and settlement. In giving the league’s support, Cooper suggested that the day could be marked as a “Day of Mourning”, an idea adopted by the Progressive Association. The following day, the Argus carried a front page report detailing the plan for the Day of Mourning.

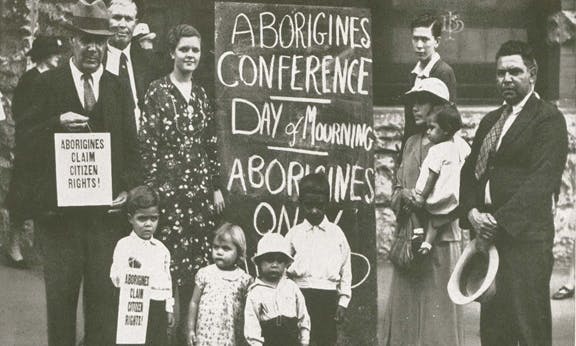

The first events were speeches in Sydney’s Domain early on 26 January, followed by the official Day of Mourning conference attended by Aboriginal delegates only. In the evening, a solidarity event with non-Indigenous supporters was held, while a fourth and final meeting was held by the Aborigines’ League in Melbourne on 31 January.

In the weeks before the Day of Mourning, the Progressive Association published a 12-page pamphlet titled “Aborigines claim citizens rights”. Written by Patten and Ferguson, the statement pulled no punches, attacking the myth of white benevolence:

“You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force. You have almost exterminated our people, but there are enough of us remaining to expose the humbug of your claim, as white Australians, to be a civilised, progressive, kindly and humane nation.”

It rejected “sentimental sympathy”, asking instead for solidarity and “for equal education, equal opportunity, equal wages, equal rights to possess property or to be our own masters – in two words: equal citizenship!”

With the Day of Mourning conference open only to Indigenous people, non-Indigenous supporters marched from Sydney Town Hall to Australian Hall on Elizabeth Street. At the hall, Patten opened conference proceedings with an impassioned speech: “On this day the white people are rejoicing, but we, as Aborigines, have no reason to rejoice on Australia’s 150th birthday”.

He explained that the purpose the Progressive Association and the Day of Mourning was “to bring home to the white people of Australia the frightful conditions in which the native Aborigines of this continent live … to put before the white people the fact that Aborigines throughout Australia are literally being starved to death … We refuse to be pushed into the background. We have decided to make ourselves heard”.

And he said of conditions on the reserves: “White people in the cities do not realise the terrible conditions of slavery under which our people live in the outback districts. I have unanswerable evidence that women of our race are forced to work in return for rations, without other payment. Is this not slavery? Do white Australians realise that there is actual slavery in this fair progressive Commonwealth?”

The Day of Mourning received considerable media coverage. Five days after the conference, Progressive Association members were invited to meet prime minister Joseph Lyons. At the meeting, Ferguson presented the association’s 10-point plan for achieving equality for Indigenous Australians, demanding aid in housing, education, working conditions, land rights and social welfare, while also calling for the federal government to take over Aboriginal affairs from the Protection Boards. The association’s proposals were ignored.

The Day of Mourning, however, remained a powerful gesture, inspiring Aboriginal people to join the struggle. Aborigines’ League and Progressive Association activists continued to organise throughout the 1940s and 1950s, organising protests and strikes and agitating for the abolition of the draconian laws that controlled every aspect of Aboriginal people’s lives.

Demanding full equality and an end to racism, exploitation and oppression, the Australian Aborigines’ League and the Aborigines Progressive Association – along with Maynard’s earlier Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association – laid the foundation for today’s Aboriginal rights movement. They continue to inspire generations of Aboriginal activists, and countless other activists, in the struggle for Indigenous rights.