What does it mean to be a Marxist?

To someone starting out in left wing politics, the movement can seem like an enormous array of labels that don’t have clear definitions, yet provoke a lot of fights. To start with, you have communists, anarchists, socialists and social democrats. Those terms alone give you plenty of heated debates about whether some famous personality is really a communist or is nothing but a social democrat, while others fight about whether some of the labels really mean the same thing – and if so, which ones. That’s before you even get on to the name-isms: Marxism, Leninism, Marxism-Leninism, Trotskyism, Maoism, to mention the big ones.

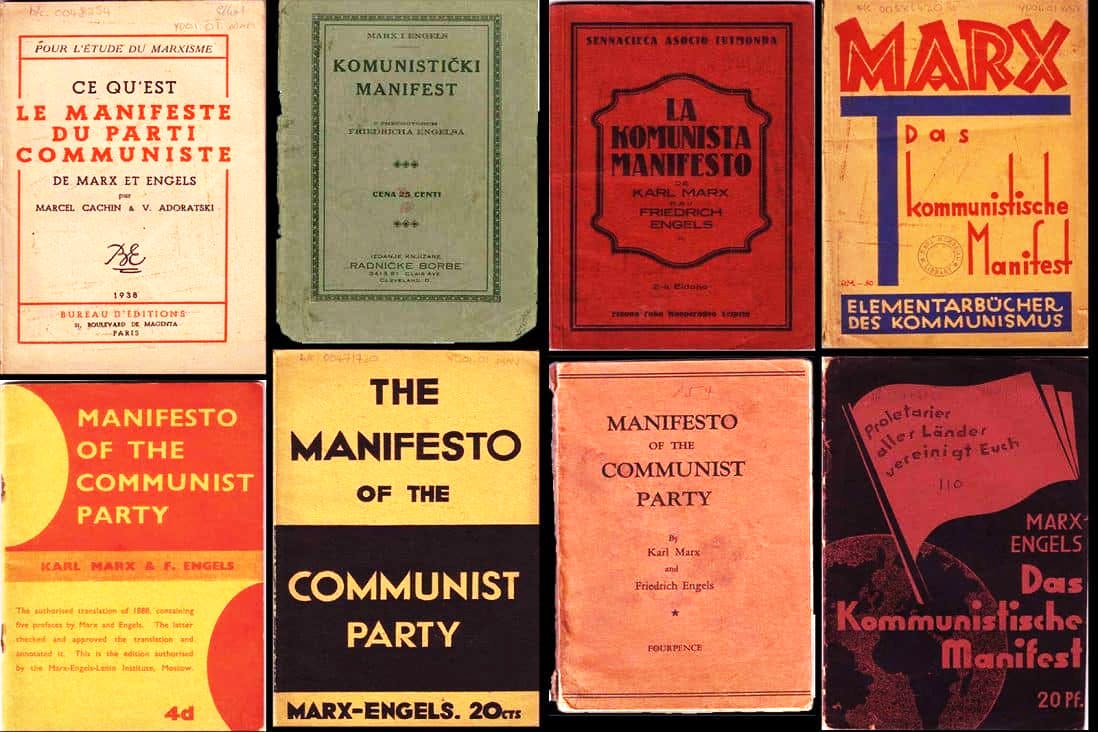

The movement to overthrow capitalism didn’t develop according to a systematic plan dreamed up by a political scientist, with neat categories to map out precisely the different parts. Its language reflects the debates of the past. Originally, a socialist was just someone who wanted society to be more equal; to many, that’s still what it means. “Communist” was a vague concept, but it broadly meant a radical socialist who wanted a revolution. It was in that spirit that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party for the mid-19th century revolutionary movement. After Stalin’s takeover in Russia, “communist” became strongly associated with the tyrannical, unequal one-party states that dominated much of the world in the 20th century. Many of us who are still for a workers’ revolution therefore prefer the term “socialist”, even though that has its own confusing legacy.

Labels are important, but they are secondary. They often disguise what matters: where you stand on the important questions of theory, strategy and politics. If an uprising happens, do you support it? Why? What do you think should happen to prevent its defeat and take it to the next level? Labels are meant to help clarify where people stand on those kinds of questions. That goes for the labels named after people as well – especially Marxist. Marxism doesn’t mean agreeing with everything Karl Marx ever said; it means building on the breakthroughs he and his collaborators made about how to understand the world and how to change it. Of course, that term has been distorted too – particularly by the Stalinist states that built enormous statues of Marx while systematically misrepresenting his world view to serve their own needs.

Marx was a theorist, educator, journalist and organiser in the movement against political repression in 19th century Europe. He joined the movement as a fighter for democracy, but soon became a “communist” – someone who wanted to smash the system of capitalism, which was at that time still a new way of organising the economy, and replace it with a society based on cooperation and equality.

He argued that this was possible only through revolutionary uprisings, not negotiations with the powerful or trust in the official political structures. He argued that revolution would require, and grow from, a struggle against all forms of oppression: for the rights of oppressed nationalities or those who suffered religious persecution, for women’s rights, for more democratic freedoms and against all those other injustices created by capitalism on top of its fundamental logic of economic exploitation. He argued that the working class had a special power and a special responsibility to fight against those injustices, to overthrow capitalism and create another world. And to achieve all those things, he was for revolutionary organisation: gathering anti-capitalist workers into organisations that could fight against oppression and lead revolutions to smash the capitalist system internationally.

Anti-capitalism has a particular meaning in Marxist politics. To a Marxist, capitalism isn’t a set of policies, or a world view based on greed and individualism. It’s a particular way of organising society based on the division and re-division of society into different classes that determine how wealth is produced and decisions are made. It’s a period in history that had a beginning and can have an ending. As Marx wrote in the Communist Manifesto, still probably the best introduction to Marxism, “modern bourgeois society” – capitalism – “has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones”.

If we understand capitalism as a period of history based on a particular class structure, we can understand how it works, why it’s special and how it can be ended. What are the classes within capitalism? The system is based on private property, so the rulers are those who own and control the property that matters to create wealth – things like factories, mines and offices. But capitalists don’t rule by divine decree, like medieval kings claimed to, and they don’t (usually) own slaves, like the rulers of the ancient world. They keep their power by making profits.

Unlike previous forms of society, capitalism creates a permanent competition within and among the ruling classes for more profit, which they get by constantly developing new production techniques, such as new machinery, and spreading their markets as far as they can. That creates a globally interconnected society based on advanced technology, a society that produces an incredible amount of wealth. It then wastes that potential by producing for profit rather than human need. It covers the world with heavily armed cops and soldiers, and equips them with ever more powerful weapons. They stand ready to oppress the working class, and to help the ruling class to settle their disputes by force, leading to violence and war.

Marx’s analysis of capitalism as a class society shows that another world isn’t just a good idea, but also a practical possibility: capitalism has, for the first time in human history, created a global community based on advanced technology, only to manage it in a destructive and inhuman way. Because capitalism is a worldwide system, Marxist theory shows that the defeat of capitalism will have to take place everywhere, as a global movement with internationalist politics that tries to build solidarity among the world’s workers.

“Marx was, before all else, a revolutionist”, as his collaborator Engels said at Marx’s funeral in 1883. In Marx’s time, just as today, there were socialists who proposed to escape capitalism either by finding their own way of living collectively within it, or by winning over governments to introduce legal reforms that would transform capitalism for the better – or both, as expressed in the popular notion of the 19th century that governments should be asked to fund workers’ cooperatives to create a better world. These ideas are a mirage. Reforms are sometimes possible and often desirable, but our enemies are the most powerful and violent ruling class that has ever existed; we won’t beat them by adjusting our own lifestyle, nor by using their tools – legislation and parliaments. There have now been hundreds of years of would-be reformers who took power in capitalist governments hoping to make a better world, only to become absorbed into the system.

There are three main reasons for this. First, to change the world for the better, the system must be reorganised for human need, not for profit. That would require ending the power of the capitalist class, which retains power by constantly accumulating profits. No ruling class has ever gone out of history peacefully and willingly, and capitalists have shown an astounding willingness to use brutality and violence to maintain their power and even just to compete with each other: bombing whole cities from Hiroshima to Aleppo, inventing and perfecting the concentration camp and using their amazing scientific capacity to expand humanity’s capacity for violence, from machine guns to napalm to intercontinental nuclear missiles. There’s no way they’ll give up their power and profit just because a government says they ought to.

Second, and related to this, parliaments are not set up to allow this to happen. They are tiny bureaucracies designed to cut off politicians from the majority of people and make them dependent on the big powers of capitalist society.

But third, and perhaps most important, if we’re going to make a new society, we have to do it ourselves. We have to go through the process of figuring out what we want collectively, organising ourselves to achieve it, renouncing the ideas that stand in our way, and defeating those who want to defend the status quo. By going through that process, an oppressed class, the members of which have been taught by capitalism to be distrustful of themselves and of each other, becomes a creative, collective movement that can organise a society based on equality and cooperation.

Through a revolution, Marx said, “the proletariat” – the working class – “rids itself of everything that still clings to it from its previous position in society ... Revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew”.

From that, we can also glean the specific Marxist conception of a communist revolution: a dynamic mass movement that allows the working class to take control of its own destiny. Revolution isn’t just about defeating the ruling class, although no doubt they’ll fight hard to stay in power, and workers will have to do whatever it takes to defend the revolution. It’s about unleashing the creative energy of the mass of people. That means it can’t be a conspiracy of a revolutionary minority. Conspiracies and coups might change the government, but they can’t transform all workers from oppressed people into confident, experienced, collective organisers of society.

Marxists argue that the working class has a responsibility to lead the socialist revolution. Marx, Engels and their supporters witnessed the so-called “industrial revolution”, when capitalism underwent a huge technological breakthrough. They saw new modern factories spring up throughout Europe. In those factories, hundreds or thousands of workers were brought into contact with each other and given the power to threaten the new ruling class that was profiting from their labour. The strikes and riots of those workers combined economic power, a drive for equality and democracy, and an ability to learn collective organising through daily battles against the bosses. Unlike the poor in medieval times, modern workers have no traditional rights to a bit of land, to relief from the church or anything else. If workers ever want any real security, they will have to overthrow the entire system and create a society with no class divide and no exploitation. They are the most potentially revolutionary class that has ever existed.

Some of Marx’s earliest insights came from the observation that the coming revolution wouldn’t be decided by machinations at the level of official politics, but from a struggle in the realm of the economy. At the same time, Engels was observing striking workers in England and predicting that when they came to lead a revolution, it would make the French Revolution look like child’s play. The workers would enact the “forcible abolition of the existing unnatural conditions, a radical overthrow of the nobility and industrial aristocracy” – that is, of the capitalists.

When this argument was put in the middle of the 19th century, it offered incredible strategic power to a communist movement that wasn’t sure how to find a real historical force that would threaten capitalism. Now, more than a century later, the working class is many times bigger and more powerful than it was in Marx’s day. Then, industrial capitalism was still being born. Now, it covers the entire globe: there are billions of workers, women and men of all different races and nationalities, capable of instantaneous global communication, and even more capable of building a new world.

For Marxists, workers had to free themselves, but they also had to free the world. They had to take up every question. Against some (in Marx’s day, often anarchists) who said the communist movement should ignore political questions, Marxists were distinguished by their argument that if workers were going to run the world, they had to understand every aspect of it, fight against every injustice and be seen by anyone who suffered as their best champion. That’s why, since Marx’s day, Marxists have been at the forefront of so many movements for equal rights and social justice: defending civil liberties and civil rights, fighting against imperialism and colonialism, pioneering the struggle for gender equality and sexual liberation. And though oppression cannot be eradicated as long as capitalism exists, Marxist strategy isn't about waiting for a communist revolution before fighting for liberation. By encouraging collective mass struggles against oppression and linking them together in a socialist workers' movement, we make the overthrow of capitalism possible.

And all that, of course, requires organisation. Marx identified a path that led from the reality of capitalism to the possibility of communism, but that didn’t mean that that transition would take place automatically. Revolutionaries must organise to fight for these ideas and build a movement based on them. In Marx’s day, he and his allies – the first “Marxists” – fought to win the socialists and militant workers of the world to these strategies: overthrowing capitalism through revolutionary struggle against all its injustices, led by the working class. They built communist groups – like the Communist League, for which Marx and Engels wrote the famous Manifesto – and even the first international workers’ organisation, which Engels later called one of Marx’s greatest achievements.

Marxists have built organisations to spread revolutions internationally, to fight against the distortions of anti-revolutionary ideas like Stalinism and reformism and to organise every struggle, big and small, that gives the oppressed more confidence to take on their oppressors. To see capitalism as a system that must be totally destroyed, to believe in international revolution, to see the working class as the only force that can lead such a revolution, to hate and fight against all forms of oppression and to organise now to make these ideas a reality – that’s the essence of Marxism.