Brazen Hussies and the weaknesses of the women’s liberation movement

Brazen Hussies, a documentary about the women’s liberation movement in Australia, gets off to a promising start. Using a vast array of archival footage, the film shows both the stultifying reality of women’s oppression in Australia in the 1960s and the exhilarating sense of hope engendered by fighting to change it. This alone makes it worth watching.

But ultimately the film disappoints. This is due, not to a fault in the filmmaking, but to its politics. Reflecting in many ways the weakness of the feminist movement itself, Brazen Hussies focusses almost exclusively on the university-educated middle-class women who led women’s liberation, and does so through the lens of the gender divide as the source of sexism.

By doing so, the film sidelines much of the fight against women’s oppression in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In Australia the movement originated from the activities of working-class militants and union organisers, many of them Communist Party members involved in the unions’ campaign for equal pay.

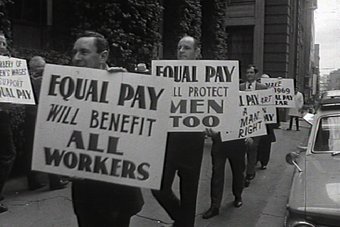

This vital campaign, accurately described in the film as “the urgent issue for women around Australia”, nonetheless gets short shrift. Despite showing footage of men and women workers demonstrating in favour of equal pay outside the Arbitration Commission in 1969, the film draws out only a single, peripheral point about it—that it was men doing all the talking in the commission, while the women workers had to sit there in silence. The vital fact is left out that, whatever their weaknesses, the trade union men presenting the case were arguing for equal pay for women while the men speaking for the capitalist class were arguing against it.

The campaign for equal pay on the job was just the most important example of working-class men fighting for women’s rights in the period covered. However, these examples don’t fit the feminist politics of the film, which emphasises instead the hostility of men to women’s liberation.

Precisely because women’s liberation emerged at a time when the left was relatively strong, when campaigns such as that against the Vietnam War suggested victories were possible, and when radical struggles for liberation in many forms were gaining ground internationally, it was initially seen as a project allied to the left and to the fundamental social change that it stood for. In 1973, when all the women workers were laid off at the Draffin-Everhot stove manufacturing factory in Melbourne, they were joined on their picket line by many women from women’s liberation and 200 workers from a nearby metal plant.

It is often forgotten that far from left-wing men being universally sexist, as Brazen Hussies portrays them, there were many who wanted to fight against women’s oppression and, initially at least, they were part of the struggle. In Adelaide men attended women’s liberation meetings until 1971, and early editions of the women’s liberation newspapers, Mejane and Vashti’s Voice, had occasional articles by men.

Nor would you know from the film that any women remained in the “male left” once the women’s liberation movement came on the scene. Certainly, none of them appear in Brazen Hussies. Yet as British socialist Lindsey German points out in her book Sex, Class and Socialism, “Many of those influenced by ideas of women’s liberation joined left-wing groups at precisely this period”. The same thing happened here. I was one of them.

Brazen Hussies is, however, an accurate reflection of the dominant ideas in the women’s liberation movement. The movement’s growth was concentrated heavily amongst students and middle-class professionals who saw gender as a more important issue than class.

The class nature of the movement is important. Its largely middle-class composition meant it was based, not on collective working-class struggle, but, like other forms of liberalism, on changing individual ideas and circumstances. This had a real appeal to a section of middle-class women, for whom changes in individual lifestyle, a fulfilling career and so on could solve many of their problems. The film reflects this composition accurately in the women who are interviewed—an over-abundance of filmmakers, artists, academics and feminist bureaucrats (“femocrats”).

Even in the 1970s, when greater common ground between women in different classes could be found because of the high degree of structural discrimination in institutions and mainstream social life, there was no bridging the class divide amongst women. This was very clear in relation to equal pay, but also around the issue of abortion. There were important arguments in the early days of the Women’s Abortion Action Campaign (WAAC) in Sydney about raising the question of free abortion on demand. It was one of the things that differentiated WAAC from the pre-existing Abortion Law Reform Association.

For middle-class women like Jeni Thornley, who is interviewed in the film about her undoubtedly unpleasant experience, an unwanted pregnancy meant going to Sydney and having the abortion at a posh clinic in Macquarie Street once you’d paid £300—the mark of the procedure’s illegality being that you had to go at night instead of during the day. For working-class women, as Communist Party member Zelda D’Aprano outlines in horrifying detail in her autobiography, it meant scraping together a much smaller sum but with much greater difficulty, and surrendering yourself to the hands of a backyard butcher.

Men demonstrating in favour of equal pay outside the Arbitration Commission in 1969.

While the film does raise some of the divisions that arose in the movement, such as its inability to engage with Aboriginal women’s struggles, it cannot explain them. Radical feminist politics, seeing gender as the fundamental divide in society, is the problem. If women as a sex are involved in a power struggle with all men, then it is logical to put aside issues of race and class.

By the late 1970s, the movement was in decline, something about which Brazen Hussies says very little. Instead, a substantial section of the film deals almost uncritically with one of the factors that hastened the transition from “women’s liberation movement” to “women’s movement”—the incorporation of the movement into welfare agencies and bureaucratic positions in newly formed government women’s departments.

Brazen Hussies spends a considerable amount of its time on the first prominent femocrat, the Whitlam government women’s adviser, Elizabeth Reid, and on the rise of WEL, the Women’s Electoral Lobby, which was devoted to feminist election strategy. While there is a passing mention that these institutions and orientations might have represented dependency rather than power, that’s it.

If anything, as the Whitlam government widened the scope for welfare activity and bureaucratic careers, the political conclusions drawn were that this was a successful strategy—that contrary to the warnings of Marxists, the oppressed might achieve their ends through the existing state machine.

And some women did make gains. Professor Ann Curthoys gives a very honest account of herself and her feminist friends rising in the world: “We published magazines, saw the correct films, attended the correct meetings, and had consciousness-raised ourselves to think correct thoughts ... Yet how did this group, these friends of mine, see themselves? They saw themselves as oppressed, as victims, as underdogs”. The reality was that middle-class feminist leaders had gained legitimacy and a foothold in the capitalist system.

The women’s liberation movement, reflecting as it did the spirit of the times, made a huge impact on attitudes in society. But it was also shaped and ultimately limited by its class basis and the feminist theories that came to dominate it.