Fractured Europe

In an increasingly illiberal world, continental Europe appears as the last bastion of moderate centrist common sense. The European Union’s defence of open markets in the face of Trump’s nativism to the west, Brexit irrationality to the north, and authoritarian state capitalism to the east, marks it out. Even the initially chaotic response to COVID-19 seemed to be resolved by the Eurogroup’s €500 billion rescue package in April. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, offers her citizens clear, scientifically backed advice on how to avoid COVID-19, in contrast to Trump’s dangerous idiocy.

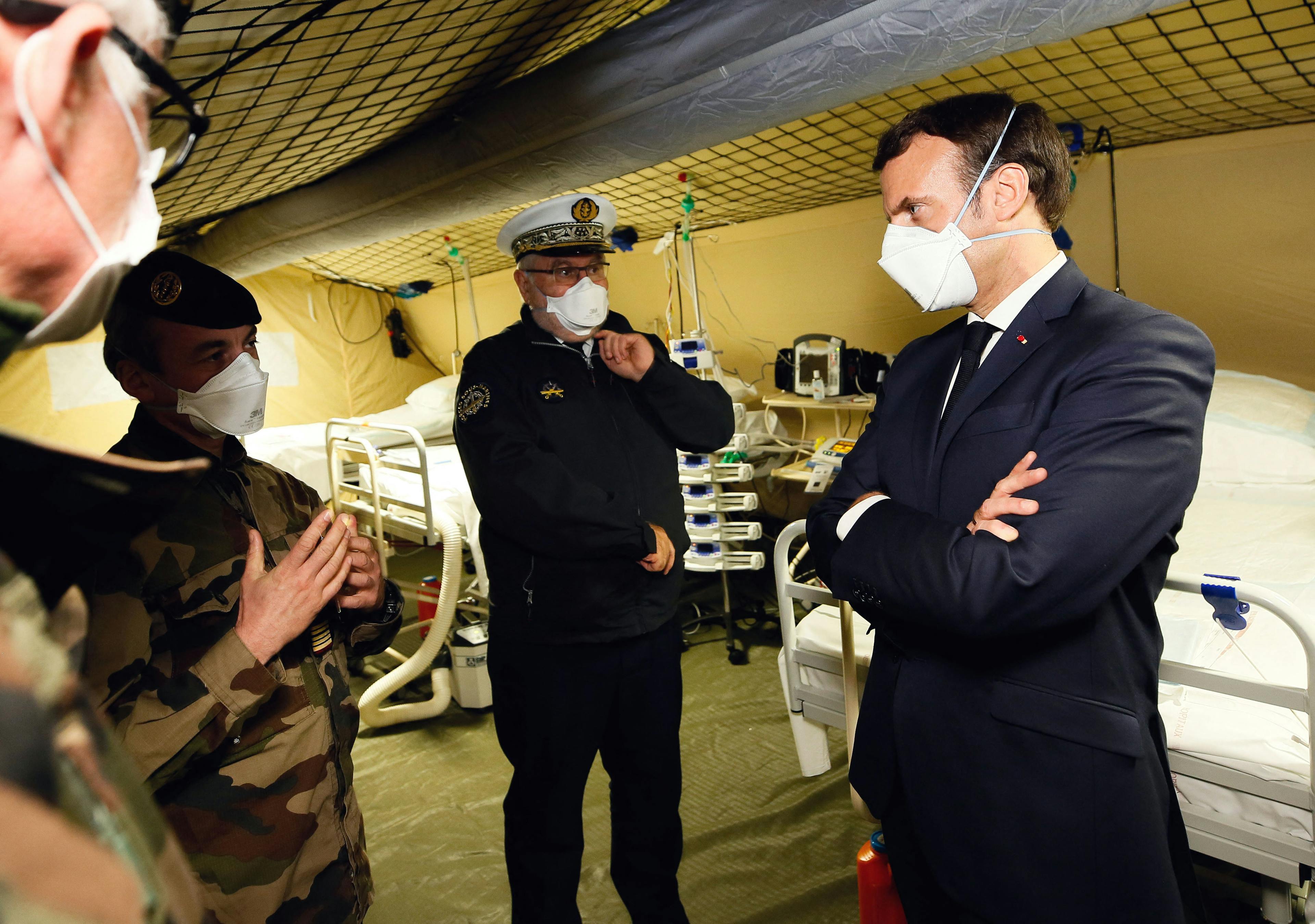

Appearances, though, are deceptive. In the face of COVID-19 and the global recession, Europe’s liberal centre is under increasing strain. French president Emmanuel Macron, whose thumping electoral victory over the right-wing nationalist Marine Le Pen was celebrated by liberals across the globe, has expressed concern in an interview with the Financial Times: “[The crisis is] going to change the nature of globalisation ... we had this feeling, that it was approaching the end of its cycle ... I believe that this shock we are experiencing, after many others, will force us to reconsider globalisation. It will force us to rethink ... sovereignty”.

Despite this, Macron believes Europe will be able to weather its current troubles. But signs so far suggest little basis for such optimism.

The debate over the euro rescue package most recently brought the tensions at the heart of the European project to the surface. After an initial 16-hour marathon meeting between European finance ministers, the negotiations broke down when the Dutch rejected giving COVID-19 stricken Italy a substantial bailout without strict assurances it would be repaid. Italy and Spain hit back, accusing the wealthier European nations of abandoning them. Agreement was reached only when Germany and France put aside their differences to propose a compromise deal that would allow relatively free access to funds for medical supplies but more stringent oversight of funds to deal with economic problems.

France and Germany, though, are split on deeper issues. France, recognising the reality that the EU is being pushed increasingly to underwrite not just the weaker states but the whole of continental Europe’s economy, is arguing for deeper political and economic integration. Germany is reluctant, worried about political backlash from its local nationalist right hostile to the wealthier European nations being burdened with the failures of southern Europe. It is a concern shared by significant sections of Germany’s ruling class as well as the “Frugal Four” of Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. Faced with this mess of hostile and counterposed national interests, the details of any further euro deals, or oversight for the agreed one, were tabled for a future meeting.

Underpinning these tensions are more deeply rooted problems, which are being intensified by the pandemic and global recession.

The current dominance of European liberalism is anchored in the nature of the European economy. Europe is “the world’s most internally integrated and globally connected region” according to the DHL Global Connectedness Index, more dependent on globalised markets and international networks of production than the US, which remains the world’s largest financial power. A study of the 2014 Global Fortune 500 list found that Europe was the only region where more than half – in fact 70 percent – of its companies’ affiliates were based overseas.

The financial crash in 2008 revealed how dependent European capitalism had become on international finance. While European leaders liked to pretend that the crisis was simply an example of Anglo-US folly, European banks had poured money into US markets. As the economic historian Adam Tooze explains in his book Crashed, by 2008 “$1 trillion, or half of the prime non government money market funds in the United States, were invested in debt and commercial paper of European banks and their vehicles”.

Before the crash hit, Swiss and German banks had started building their own US-based mortgage companies to buy directly into the housing market. While much discussion has focused on US-China financial relations, Tooze points out that the “central axis of world finance was not Asian-American but Euro-American. Indeed, of the six most significant pairwise linkages in the network of cross-border bank claims, five involved Europe ... it was the spinning motion of this transatlantic financial axis that impelled the surge in financial globalization in the early twenty-first century”.

The formation of the European Union was one of the most significant achievements of the neoliberal era. The post-WWII economic boom and the surge of international finance and production from the 1970s on helped make it possible. Before this, the trend was for businesses to concentrate their wealth within their own national borders with the help of nation-states.

The crisis of the mid-1970s forced a radical restructuring of this arrangement. “The number of European mergers increased significantly” in this period, argues Christakis Georgiou in International Socialism. “The figures for mergers and acquisitions concerning Europe’s 1,000 largest firms show significant developments during the 1980s. In 1982-3 there were 117 mergers. The figure rose to 303 in 1986-7 and 662 in 1989-90. In the early years of the decade national deals predominated. This changed by the end of the decade. In 1983-4, 65.2 percent of the deals were national, 18.7 percent European and 16.1 percent international. By 1988-89 only 47.4 percent were national deals, whereas 40 percent were European and 12.6 percent international.”

This provided a material incentive for European economic integration. The result was the creation of the Common Market and the euro to facilitate the strengthening of a Europe-wide economic bloc able to compete with the US and a rising Asia.

To oversee integration, a vast bureaucracy was created, with the European Central Bank at its heart. Around it, other institutions of the EU were constructed: the European Council, the European Parliament and the Court of Justice. These gave a democratic veneer to what was in reality a massive centralisation of power in the hands of the European Central Bank, which was increasingly divorced from any democratic pressure.

There was resistance to this process. When European integration was put before the public, it was repeatedly rejected. In 2001, Irish voters rejected the treaty of Nice, only to be bullied into accepting it in a second vote several months later. This was repeated in 2008 with the referendum over the treaty of Lisbon. In 2000, Danish voters rejected joining the euro, as did Sweden in 2003. The enormous protests in 2001 at Genoa, Italy, revealed that a significant section of young students and workers were open to fighting against the neoliberal agenda behind the EU.

And despite talk about a future Europe-wide super state, nation-states continued to play a central role. While European businesses were increasingly integrated regionally and globally, they still looked to particular nation-states for help. When debates broke out over the future of the European Union, capitalists lobbied the government they had a primary relationship with. Governments in turn were concerned about their particular national businesses and sought to protect them as much as possible. So in 2008, the Italian government stopped Air France from taking over the Alitalia airline, only to turn around and sell it to an Italian financial group. The French responded by orchestrating the merger of Gaz de France and Suez in order to block a takeover bid by the Italian energy company Enel.

Contestation over the euro is similar. As the Marxist economist Guglielmo Carchedi has explained, Germany and northern European states generally favour a stronger euro because this benefits their concentration of innovative high tech firms, while export-dependent countries like France and Italy prefer a weaker euro to stimulate exports. These antagonisms could be managed so long as a crisis didn’t bring things to a head.

Now crisis is upon us. Significant changes in the balance between nation-states and global markets are under way. International production chains have broken down under the strain of the COVID-19 crisis, and even before that, foreign direct investment was slumping and world trade contracting.

For the leaders of European capital, this raises a series of seemingly intractable problems. If “globalisation has to change”, as Macron states, then what will this mean for the highly globalised European economy? If international production chains have to be restructured to better suit the interests of particular nation-states, how will this be organised in an integrated Europe that is in a much worse position to take such steps than the industrial powerhouses of the US and China? What will the future of the EU be in an increasingly nationalistic world?

These problems are not new. The so-called “sovereign debt” crisis of 2010 already revealed the division between the poorer southern European states such as Greece, Spain and Italy, and the wealthier northern countries. Mass protests and general strikes against austerity rocked the continent for years. At the same time, the far right has grown.

While battered and bruised, the liberal centre has been able to hold the line against these challenges, but the underlying problems of inequality and democratic deficiency have not been solved.

On the economic front, the EU has been making moves towards more protectionist measures for years. This has particularly focused on China, which the European Council described in 2019 as a “systemic rival” to the EU. While Germany traditionally promoted a Wandel durch Handel (change through trade) policy in regard to China, it has increasingly taken a tougher stand. Following the Chinese takeover of German robotics company Kuka in 2017, Germany has blocked a series of high profile takeover bids from China, most notably Leifeld Metal Spinning in 2018.

However, Europe’s ideological commitment to free market competition, as well as the material influence of Chinese investment in the continent, has created tensions. In 2019 the European Commission blocked the merger of Siemens and Alstom, which would have created a new massive European railway company to compete with the China Railroad Rolling Stock Corporation. The commission’s decision was attacked by the French economy minister, Bruno Le Maire, who accused the commission of “serving the economic and industrial interests of China, instead of defending the interests of Europe”.

The demise of the EU has been predicted so often it is easy to respond with scepticism to a new round of hand-wringing over the future of European integration. While powerful forces are undermining the material basis for European quasi-unity, the sheer weight of the inertia produced by the status quo shouldn’t be underestimated. Even those parties that position themselves as the most rigorous critics of the political centre are shaped by the reality of Europe’s political economy.

So the far right, while decrying the bloated bureaucracy in Brussels, have sought more pragmatic solutions the closer they have come to power. Both Marine Le Pen in France and the right in Italy had to moderate their anti-EU stance as the possibility of electoral victory became more real. On the left, the left-wing Syriza party in Greece capitulated to pressure from the EU once in government.

There are, however, limits to this inertia. Buying time can work for years, sometimes decades, but it builds up huge problems in the long run. We’ve seen this before. In the inter-war period, European liberals and social democrats promoted trade liberalisation and the gold standard as economic common sense. When the Great Depression hit, and the needs of their national capitalist classes changed, the same politicians junked their previous beliefs and embraced trade wars and protectionism.

Every future scenario being discussed comes with serious dangers for European capitalism. Its end may not be in sight, but what is emerging is a further fracturing of the continent on global, national and class lines.

Before the pandemic hit, we saw an inspiring revival of working class radicalism across France. The mass deaths and economic shock over the last couple of months will undoubtedly breed increased discontent with Europe’s ruling class. This gives some hope for, at some point, a new wave of struggle that can shift the balance of forces away from Europe’s rich and powerful and toward those who have suffered for their system for too long.