The Australian communist in the thick of Sri Lanka's independence movement

With every Australian government in recent years obsessing about repelling Tamil asylum seekers from Sri Lanka, one could be forgiven for thinking the interests of ordinary people in the two countries are diametrically opposed. That’s why it’s worth remembering the role played by an Australian activist in the struggle for independence and social justice on the island.

On 4 April 1936, Mark Anthony Bracegirdle arrived in Colombo to work on a tea plantation at a place called Madulkelle in the central highlands. In Ceylon, as the British called the colony, the plantations operated almost as a closed kingdom. Bracegirdle had been offered a post as a “creeper” – a name given to assistant planters because of the obsequious demeanour they were supposed to adopt to the periya dorai (“big master”).

Creepers could, if they behaved themselves, work their way up the white hierarchy, eventually obtaining privileges and status they’d never have enjoyed in their own countries. But their success depended on their management of the estate labourers, who were themselves stratified in a rigid order. The plantation system rested on a workforce of so-called coolies, impoverished Tamils brought from India by recruiting agents who controlled the distribution of their wages. The system guaranteed grotesque abuses, with coolies housed in segregated barracks, denied education and often sinking deeper and deeper into debt.

In later life, Bracegirdle claimed he’d come to Ceylon because of an interest in agricultural improvement – specifically, a new method of controlling weeds. But he was no ordinary agriculturalist. Mark Bracegirdle was a committed communist. In England, his mother Irma had supported the suffragists, stood for the Independent Labour Party and campaigned for the unions during the 1926 general strike. When she and her children moved to Australia, Mark studied painting and gravitated to the fringes of Melbourne’s bohemian and radical circles. He became friendly with John and Sunday Reed and the artists associated with Heide – the property in Bulleen on which the Reeds cultivated modernist painting. He also joined the Young Communist League.

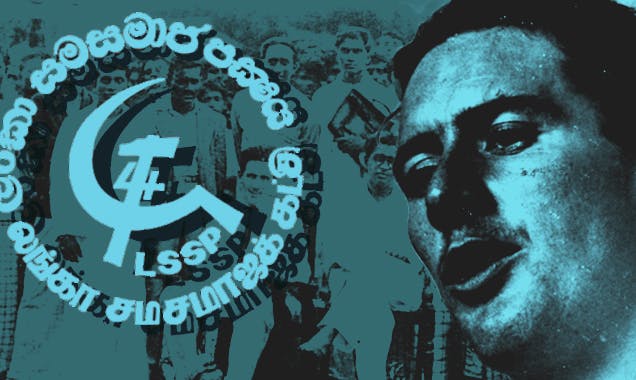

When Bracegirdle applied for a passport to travel to Colombo, the Australian authorities knew of his politics. But they let him go, the Commonwealth Investigation Bureau deciding that a stint in the colonies might prevent the young man joining “the ranks of aggressive communism”. It was a serious misjudgement. Once on the plantation, Bracegirdle noted immediately that his superintendent forced the coolies to work even when they were sick, while preventing them from educating their children because literacy would “give them ideas in life above their station”. Within six months, he had contacted the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), a newly formed group agitating for independence and socialism.

A policeman who encountered Bracegirdle at the home of an LSSP member around that time described him as “a well-made, good looking young man of about 24 years of age [with] very regular features and a charming smile ... His hair is dark brown and in large waves, and his eyes are greenish blue”. Even while admiring the Australian’s profile (“rather like the poet Rupert Brooke”, he decided), the officer found Bracegirdle’s views alarming, judging him “strongly Communist and decidedly anti-British” and noting that he spoke with great bitterness about the “atrocities of British imperialist methods” in suppressing riots in 1915.

Worse still, he was wearing a sarong. Though Bracegirdle’s association with the LSSP worried the authorities, “it was the likelihood that he would ‘probably go as far as to adopt the national dress’ that put him beyond the pale”, Alan Fewster explains in The Bracegirdle Incident. “This social crime was worse than it sounded, inasmuch as it was final proof that a white man had ‘gone native’ ... [Here] was a case of a European going native in the most public way imaginable and, what was worse, he seemed proud to be doing so.”

By December, Bracegirdle was a member of the LSSP; the next year, he was co-opted to its central committee. LSSP leader Dr N.M. Perera concluded a meeting of 2,000 coolies at Nawalapitiya, a central plantation town, by declaring: “Comrades, I have an announcement to make. You know we have a white comrade. [applause] I call upon comrade Bracegirdle to address you”. In his speech, Bracegirdle declared his compatriots to be bloodsuckers and urged his listeners to “rise and win your freedom and gain your rights!”

A government official in the crowd later expressed his horror at Bracegirdle’s presence and his attack on the planters, particularly because he “claimed unrivalled knowledge of [their] misdeeds ... and promised scandalous exposures”. In his notes, the official recorded that Bracegirdle’s “delivery, facial appearance [and] his posture were all very threatening” and that, worse still, workers “were heard to remark that Mr Bracegirdle has correctly said that they should not allow planters to break labour laws and they must in future not take things lying down”. Another observer recorded that the emotions of the labourers “were roused to a very high pitch”.

This could not be allowed to stand. “It is clearly dangerous to allow a European youth of this type to remain in Ceylon stirring up feelings against employers of labour and against the British government”, the deputy governor declared. Sir Edward Stubbs, the governor, duly signed, under obscure wartime legislation, an order-in-council giving Bracegirdle 48 hours to “quit the island” by the next available ship.

The LSSP had other ideas, launching a campaign to repeal the order, claiming, with some legitimacy, that the method could exile anyone “without trial, charge or cause and without the possibility of any appeal to authority”. Meanwhile, Bracegirdle went into hiding, including briefly living in a cave behind his old estate. In an increasingly polarised atmosphere, the Times of Ceylon, the newspaper of the planters, ran the headline: “BRACEGIRDLE MUST BE BUNDLED OUT NOW: ARREST THE REDS WHO FLOUT THE LAW”.

Rather than being bundled out, Bracegirdle surfaced at an open-air meeting, where he delivered solidarity greetings from “the workers of Australia” and warned that “the capitalists and imperialists were preparing for war, and in the event of war it will be the workers who would have to face the war and suffer”.

On May Day, 10,000 LSSP supporters marched behind banners reading, “We want Bracegirdle” and “Deport Stubbs”. A few days later, they organised a rally of 50,000 people. Unexpectedly, those present noted “a commotion among the crowd and, as from nowhere came running Mark Anthony [Bracegirdle] wearing a white suit and a blood red shirt and tie to match”. The Times dubbed the rally a “sedition-mongers field day”, explaining disgustedly that Bracegirdle told the crowd that he had “sat with planters who have in the evening quiet decided where they should kill and shoot certain Sinhalese on this island”. (A voice in the crowd responded, “Down with the blackguards!”)

He also assured those in attendance they were the “only instrument of Ceylon’s freedom” and promised, as their comrade in arms, to publicise their cause to workers around the world. His speech concluded with a reference to “those drunken countrymen of mine”, whom he dubbed “more dangerous than a scorpion” and said “should be trodden on”.

Bracegirdle was arrested by police with drawn truncheons at an LSSP property soon after. Yet the political crisis facing the authorities continued to intensify. Already, the governor had been forced to endure the ignominy of a vote of censure successfully moved by the LSSP in the state council. Now, the LSSP’s lawyers contested the legality of Bracegirdle’s arrest in sensational hearings before the Supreme Court. On 18 May, the judges handed down a decision that Fewster calls “a triumph for Bracegirdle and his team”: the order-in-council was illegitimate and the prisoner was to be released. When Bracegirdle eventually left Ceylon in October, he did so as a free man whose civil rights had been upheld.

The ramifications of the so-called Bracegirdle affair continued to be felt long after, the incident destabilising the colonial authorities and helping to transform the LSSP into a mass force. The LSSP’s formal embrace of Trotskyism in 1940 raises fascinating questions about Bracegirdle’s own loyalties and motivations. Originally committed to independence and a loosely defined socialism, by 1937 the party was increasingly led by young intellectuals who had learned their politics in Britain, where some had encountered Trotsky’s ideas. Philip Gunawardena, Leslie Goonewardene, Vernon Gunasekera, Colvin R. de Silva, Edmund Samarakkody and others were initially known as the “G Group” before becoming, on the basis of their Trotskyism, the “T Group”.

Bracegirdle, on the other hand, was known in Australia as a fervent Stalinist, who had once divested himself of a treasured collection of Diego de Riviera’s art when the muralist attacked Stalin. Members of the T Group apparently came to believe that he’d been sent to Ceylon as a Comintern agent, Samarakkody writing in 1960 that Bracegirdle “was the first person to sow the seeds of Stalinism in the party”.

But that might have been a retrospective projection. Certainly, when Bracegirdle first arrived, the intellectually precocious LSSP leaders judged him theoretically weak rather than thinking him any sort of ideologue. Gunasekera and the others even helped write many of his speeches. It seems likely that, whatever his reasons for coming to Ceylon, Bracegirdle was genuinely moved by the plight of the coolies he sought to organise.

Intriguingly, after leaving Ceylon, he made his way to Berlin, where he appears to have been involved in smuggling Jewish refugees out of Nazi Germany. Details of this, and other aspects of his later life, remain disappointingly sketchy. The obituaries published on his death in 1999 noted only that he became a conscientious objector during the Second World War, helped organise a flying doctor service in Zambia and then settled in Gloucestershire, England, where he remained a committed Labour Party member.

Historians of the independence movement in Sri Lanka regard the Bracegirdle incident as an important moment in the freedom struggle and a major boost to the forces of the left. But even though the press in Australia (and, indeed, around the world) devoted considerable coverage to the episode, Mark Bracegirdle remains largely unknown in this country. That’s a shame. In an era in which Australian chauvinism justifies the most appalling brutality against oppressed workers fleeing Sri Lanka, the kind of anti-colonial solidarity that he voiced back in 1937 matters more than ever.