Today’s note is a bit long, but Paul Krugman and scores of other liberal economists in recent weeks have written troves of articles about how much Donald Trump’s tariffs will make the US and the world poorer. They have been accompanied by entreaties not to sane wash or search for a rational kernel in the president’s economic doctrine. (Krugman considers the tariff announcement the latest example of the new administration’s “broader pattern of malignant stupidity”.)

But as barmy as it might seem, there is a rationality in Trump’s Rose Garden announcement of “reciprocal” tariffs, albeit not the one found in the economic justifications his team is making for their so-called Liberation Day policies. It’s the logic of confrontation embraced by a state locked in a (perceived) losing battle with a peer competitor.

To understand it, Nikolai Bukharin’s 1915 work Imperialism and World Economy is worth revisiting. In a remarkably straighforward argument, he explains how the contradictions inherent to capitalist economic development are successively displaced to higher levels with the increasing concentration and centralisation of capital, laying the basis for conflict between states. If you ignore Trump’s waffle about making America rich again, the central thrust of his actions fit with the classical model of imperial confrontation in which wealth generation is subordinated to geopolitical considerations such as a struggle for survival or supremacy.

Despite the simplicity of his argument, Bukharin presupposes familiarity with the basic functioning of the capitalist economy and with the concepts developed in Karl Marx’s Capital. So to outline the broader logic of Bukharin’s argument, I’ll first review the basic outline of capitalism provided by Marx (which Bukharin draws on), and then outline Bukharin’s argument that the economic logic of protectionism is part of a broader tendency of inter-state confrontation in a globalised capitalist economy.

Apologies that what follows simultaneously manages to be both truncated and longwinded. If you are familiar enough with Marx, skip the first section. If you are familiar enough with Bukharin, skip to the last section dealing with Trump and the current moment—although if you are that familiar, you probably already know what I’m going to say, so maybe skip the whole thing.

Fundamentals of the capitalist economy

Whenever human beings work for one another in any way, their labour acquires a social form; in other words, whatever the form of connections established between producers, whether directly or indirectly, once a connection has been established and has acquired a stable character, we may speak of a system of production relations, i.e., of the growth (or formation) of a social economy.

Isaak Rubin Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value (1928)

Every society is founded on a network of relationships called a social division of labour. It’s the economy—the mechanism through which human needs are met and on which any other human institution is premised, from the family to the state. The capitalist economy is a unique and highly productive division of labour. In our society, companies and corporations are the fundamental economic units; production is organised privately, without economy-wide planning; businesses compete against each other, rather than collaborate; and the goods and services created take the form of commodities—things produced for a market rather than direct consumption. (A market is a venue or platform that facilitates the exchange of goods and services between buyers and sellers.)

Capitalism is the first system in history to draw most of the planet’s population into economic interdependence. This is not immediately obvious, because most economic relationships between people are created indirectly through the exchange of commodities. For example, we don’t usually interact directly with the people who have sewn our clothes, assembled our appliances or refined our petrol. Instead, through market exchanges, the commodities act as surrogates—we come into contact with people indirectly through the things they have created. (The act of buying petrol, for example, connects us with thousands of people, from those working the wells in the Middle East, to the dockers and seafarers responsible for transporting the crude oil … and so on, all the way up to the person taking our money in the service station.)

Each item—each commodity—must satisfy a want or a need. Otherwise, it couldn’t be sold in a market. So commodities must have “use-values”—some particular quality that makes them beneficial to a buyer (a simple example: a cup’s use-value is its capacity to facilitate the drinking of liquids). Yet capitalist markets aren’t designed primarily to satisfy needs; the exchange process assigns to commodities economic values that have nothing to do with their usefulness.

Fundamentally (at least for our purposes of understanding the economy), market exchange is about comparison. For example, when we say that $1,000 will buy this computer or that lounge suite or x litres of petrol, we are comparing the economic value of things rather than their particular use-values. They cannot meaningfully be compared as material goods because they don’t share common physical qualities—they have different sizes, colours, weights, uses, atomic compositions. If you try to understand the exchange process through the prism of use-values, you are “comparing apples with oranges”, as a statistician might say.

The exchangeability of commodities is based on their sharing of a common social quality, something Marx referred to as “congealed labour-time”. The basis of economic value is the labour expended in production. Specifically, it is socially necessary labour time—the average time it takes the average skilled worker, using the standard technology in any particular industry, to produce a useful thing. “Value” is the social average and is expressed in prices. While the magnitude of value is determined by socially necessary labour time, the content of value is not any particular (or “concrete”) labour, but what Marx called “abstract labour”. What appears to be a constant trade in useful things is a process through which the different labouring activities of businesses are measured against one another. Labour takes the form of value only because of the comparison, and therefore equalisation, of qualitatively different labouring activities via the systematic trade in billions of different commodities.

Competition between the producing companies alters the values of commodities and determines how the created value is distributed. The commodities produced by the most efficient companies (those that create goods or services using less labour time than is socially necessary) still sell for the price that expresses the average labour performed in a particular industry. But these firms take a greater share, relative to their labour performed, of the total sales revenue accruing to an industry; they obtain a “super-profit”. Alternatively, the most productive firms reduce their prices to sell more goods while making the same return per unit of output as their competitors; they increase their market share, and their total profit rises. Firms with less than the average output per hour, or with higher than average costs, risk being pushed out of business. As a result, there is a never-ending quest to increase productivity through technological change (to increase the total amount of things produced while decreasing the amount of labour expended in the production process). This is a key aspect of what is called the “law of value”.

Within an industry, the exchange of commodities allows quantitative comparisons—what matters is the differing productivity levels between firms carrying out the same labouring processes (i.e. producing the same products). For example, the basic questions for a garment manufacturer relate to how many shirts the business produces per year and at what cost compared to other shirt companies.

At the economy-wide level—the totality of industries—it’s not only commodities of the same type being compared through the exchange process, but the qualitatively different labouring processes creating a vast array of things—shirts, steel, pens, paper, hamburgers, services etc. Competition at this level shifts investments from one industry to another in a national economy. While some firms may be more efficient than others in one industry, some industries, due to uneven technological progress or to the particular natural resources available, are more efficient than others. So just as differing levels of productivity allow some firms to capture a greater relative share of the value produced in a particular industry, the price movements of different commodities allow whole industries to obtain a super profit—to capture a greater share of the total value being produced economy-wide. Russian Marxist Isaak Rubin put it this way nearly 100 years ago:

The increase of productivity of labour changes the quantity of abstract labour necessary for production. It causes a change in the value of the product of labour. A change in the value of products in turn affects the distribution of social labour among the various branches of production. Productivity of labour—abstract labour—value—distribution of social labour: this is the schema of a commodity economy in which value plays the role of regulator, establishing equilibrium in the distribution of social labour among the various branches of the national economy (accompanied by constant deviations and disturbances).

Equilibrium, however, can only be fleeting. Disequilibrium is the natural state of a capitalist economy; commodity values, and therefore prices, are ever-shifting because individual firms constantly try to increase their efficiencies and lower their costs. The market “works” by adjusting the distribution of labour across the economy according to these disparities in productivity. So while prices express values, they also systematically diverge from them to varying degrees because of the unplanned nature of production.

British Marxist Chris Harman used the analogy of ocean tides to make the point: they move from high to low, but oscillate around some median level. In an economy, the median need not strictly reflect productivity levels. If there is a shortage of, or increased demand for, a particular commodity, its price will rise above its value, spurring investment into that industry to increase output; conversely, if there is oversupply, the price may fall below its value, and investment will decline. Usually this will be temporary because investment and output often adjust relatively quickly.

These processes are driven by the indirect and external power of the market, which compels business owners to accumulate ever more value, in the form of capital. “Capital, being self-expanding value, is essentially a process, the process of reproducing value and producing new value”, Ben Fine and Alfredo Saad-Filho write in Marx’s Capital. “In other words, capital is value in the process of reproducing itself as capital.” Capital comes to dominate social life, as the competition between firms to increase output and reduce costs informs all decision-making related to the reproduction of society. This is what makes capitalism so “expansionist”. As Marx and Engels wrote in the Communist Manifesto:

The markets [keep] ever growing, the demand ever rising … [Capitalism] has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment” … It has resolved personal worth into exchange value [a price], and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom—free trade.

While the market is felt as an impersonal and external coercive force, there is a very personal and direct relationship of economic domination at the base of it all—the exploitation of labour in the workplace. The economy is not simply a collection of businesses; each firm is internally divided between a class of workers and a class of owners and managers—a minority who own or control the vast majority of the productive apparatus required to produce the things we all need: the telecommunications infrastructure, the agricultural land, the machinery, the office blocks, the factories, the mines and so on. They also own and control the commodities produced.

The relationship in the workplace is personal because, unlike interactions in the market, the manager is a direct overlord. In the market, commodities are representatives of those who have produced them; in the workplace, the manager is the personification of capital, imposing on the worker the dictates of the market. Using the gestures and language of a fellow human, the manager impels the worker to act as an automaton and directs them to repress their own needs in the name of efficiency.

For production to proceed, business owners must hire workers to create useful products—to perform the “concrete labour”. The worker may be a “subordinate”, but they are not a commodity. It’s their capacity to labour—their “labour power”—which is purchased by the boss, along with raw materials, machinery, etc. When a firm’s products are sold, the revenue returns to the business to pay for production costs. But every firm requires its revenue to be greater than the money originally outlaid. This extra value goes to executives, to shareholders, to the state as taxes and to banks as interest on loans. Part of it is retained for reinvestment to expand operations. But where does the difference come from between the total money spent on production and the profit remaining after the commodities are all sold? The answer is that, while all the inanimate inputs of production pass on the value embedded in themselves, labour power not only transfers its value, but creates new, additional, “surplus value”.

A worker might get paid for eight hours’ work, but the value created in that eight hours must surpass the value of the wage (the socially necessary labour time required to reproduce the commodity labour power, expressed as a price). That’s capitalism’s great “secret”—the mechanism through which the accumulation of capital—the self-expansion of value—occurs. It’s not just that a firm, an industry or a national economy can gain a competitive advantage and realise a greater share of value through the market. The “prime mover” of value creation is exploitation at the point of production. This is hidden beneath the exchange process and the fiction of “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work”—it is impossible to say precisely how much value workers surrender to the capitalist class.

Once the basic mechanism of exploitation is understood, “productivity” takes on a more precise class meaning: an increase in the extraction of surplus value, an increase in the number of commodities produced in a day, by workers. Sometimes this is achieved by making people work longer hours. Usually, it involves greater mechanisation/computerisation of the labour process to allow a worker to process more raw materials or data in a given time. Productivity increases and reductions in labour costs are the primary ways firms, industries and national economies compete. So competition and exploitation are linked—to be more effective at the former means increasing the latter.

Bukharin’s presuppositions

The foregoing gives us enough overview to relate the results Bukharin built on or presupposed.

First, capitalist efficiency has its flipside in endemic economic crises. They take different forms, but underlining each is that the creation or realisation of value, or the extraction of surplus value, butt up against limits created by the accumulation of wealth. “The economy may be seen as a system of expanding circuits linked together like interlocking cogwheels”, Ben Fine and Alfredo Saad-Fihlo write (Marx’s Capital again), highlighting the interconnectedness of the capitalist economy. “If one set of wheels slows down or grinds to a halt, so may others throughout the system … It is the necessary but unplanned and competitive interlocking of capitals that leads Marx to talk of the anarchy of capitalist production.”

Crises can result from business owners accumulating tremendous wealth and deciding not to reinvest it, at least for a time. They can result from overinvestment and, as a consequence, an overproduction of goods that can no longer be sold. They can result from the market’s natural disequilibrium reaching proportions that produce a shock withdrawal of resources from the market. At these times, we’re inclined to talk about “market failure”—hundreds of thousands of homeless people yet millions of empty homes, millions starving while food is left to rot, for example. But these economic crises are not really “failures”; they are the system adjusting to disproportionalities arising from its unplanned nature. Ironically, crises signify that the market is working.

The most important aspect of systemic crisis, however, is not related to the subjective decisions of business owners or the cyclical movements or abrupt adjustments of the market. It is rooted in production. With technological advances, the number of commodities increases, but the value embedded in each declines because outlays on the value-creating commodity, labour power, decrease as a proportion of the total investment of an industry. The result is a tendency for the rate of return on investment to decline over time, which can lead to instability, stagnation and often underpins economic depressions, during which value creation turns to value destruction. (For an explanation, see chapters eight and nine of Ben Fine and Alfredo Saad-Filho’s Marx’s Capital.)

Second, industry expands faster than agriculture and there is a rift between town and country. As Marx noted in Capital (part 4, chapter 14, section 4): “The foundation of all highly developed divisions of labour that are brought about by the exchange of commodities is the cleavage between town and country. We may say that the whole economic history of society is summarised in the development of this cleavage”. The main reason for this is that capitalist production is intensive—huge amounts of machinery and technology are concentrated in cities to facilitate the greatest accumulation and the fastest pace of exchange.

Third, competition and crises lead to the concentration and centralisation of capital. Concentration refers to businesses becoming larger as they invest in machinery and expand production. Centralisation refers to the process through which the smaller or less competitive firms are taken over, and fewer and fewer business owners come to control larger sections of the economy. With greater concentration and centralisation, monopolies develop—companies dominating entire industries—and free trade is turned to its opposite. Bukharin notes several forms, such as joint stock companies, cartels, syndicates and trusts. The central dynamic underlining each is the same:

The process of the formation of capitalist monopolies is, logically and historically, a continuation of the process of concentration and centralisation of capital. Just as the free competition of artisans, arising over the bones of feudal monopoly, led to the accumulation of the means of productions in the hands of the class of capitalists as their monopoly possession, so free competition inside of the class of capitalists is being more and more limited by restrictions and by the formation of giant economies monopolising the entire “national” market. Such giant economies must by no means be considered “abnormal” or “artificial” phenomena.

Through this process, they streamline operations and regulate production and exchange to their advantage, putting a break on the competition that fosters technological advance and manipulating the law of value to mitigate against market cycles and crises. Richard Day and Daniel Gaido write in Discovering Imperialism:

By restricting output in relation to demand, organised capital could artificially raise the profits of cartel members at the expense of unorganised enterprise; the total surplus value would then be redistributed to the largest firms, with the result that ‘cartel profit’ represented “nothing but a participation in, or appropriation of, the profit of other branches of industry”.

Monopolies don’t form across only one industry. Firms can integrate many aspects of their operations across different branches of production by taking over suppliers, transport and logistics networks and “downstream” processors. (Rudolph Hilferding, an Austrian Marxist writing before Bukharin, noted that concentration and centralisation intertwine banking and industrial capital into a new form: finance capital.)

Fourth, it’s not just that concentration and centralisation/monopoly undermine free competition—the impersonal market character of economic interactions grows over into direct confrontations that begin to assume an extra-economic character. The large firms engage in industrial espionage, take control of raw materials so that rivals can’t access them, deny them access to credit, etc. As Lenin wrote in his 1917 pamphlet Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism: “There is no longer a competitive struggle between small and large, between the technically developed and the technically backward. We see here the monopolists throttling all those who do not submit to the monopoly, to its yoke, to its dictation”. The most well-known example of this in his and Bukharin’s day was US Standard Oil, a trust eventually sued by the Department of Justice for engaging in espionage, discriminatory practices and unfair methods of competition.

Finally, the state comes to play a decisive role in economic life. Often, “state” and “market” are considered somehow counterposed. But they have been intimately linked from the beginning. For example, Marx, in the second chapter of Capital, noted that even the most basic act of exchange presupposes a contract:

In order that these objects may enter into relation with each other as commodities, their guardians must place themselves in relation to one another … and must behave in such a way that each does not appropriate the commodity of the other, and part with his own, except by means of an act done by mutual consent. They must therefore, mutually recognise in each other the rights of private proprietors. This juridical relation, which thus expresses itself in a contract, whether such contract be part of a developed legal system or not, is a relation between two wills, and is but the reflex of the real economic relation between the two.

Capitalist markets, which operate as external coercive forces, have always been structured and regulated by state power, which creates a regime to ensure the smooth functioning of economic life and a (somewhat) level playing field between businesses—anti-trust laws, labour laws, tax regimes, incorporation procedures, a national currency, shared infrastructure etc. It mediates between businesses and sometimes disciplines individual firms for the capitalists’ collective interest. As such, the capitalist state’s growth is closely related to the economy’s expansion. Marx and Engels noted:

The capitalist class keeps more and more doing away with the scattered state of the population, of the means of production, and of property. It has agglomerated population, centralised the means of production, and has concentrated property in a few hands. The necessary consequence of this was political centralisation. Independent, or but loosely connected provinces, with separate interests, laws, governments, and systems of taxation, became lumped together into one nation, with one government, one code of laws, one national class-interest, one frontier, and one customs-tariff.

The overall picture of capitalist development is one in which the economy is competitive, expansionist, increasingly integrated and crisis prone. As the business units develop and become larger, a small number dominate. Economic competition frequently grows into non-economic competition, favouring the most powerful and connected firms. This is not anti-capitalism: economic development is always characterised by non-economic interference. Capitalism is facilitated and structured, not retarded, by the growth of national state institutions, which also act to discipline those firms undermining the “greater good” of the economic life of the nation. Bukharin outlines how these processes are displaced to the international level and lay the basis for conflict between nationally based capitalist groups.

World economy

The capitalist economy is world economy—in Bukharin’s words, “a system of production relations and, correspondingly, of exchange relations on a world scale”. So the social division of labour is an international division of labour. For example, when we look in our kitchen cupboards, wardrobes, garages and so on, we find products of labour performed worldwide. Whether it’s a pencil and notebook, a packet of two-minute noodles, our shoes, the TV or phone, the bike or car, the packaging of anything, almost everything results from chains of labour spanning the globe. In this way, nothing is really “local” anymore. Bukharin writes:

Just as every individual enterprise is part of the national economy, so every one of these national economies is included in the system of world economy. This is why the struggle between modern national economic bodies must be regarded first of all as the struggle of various competing parts of world economy—just as we consider the struggle of individual enterprises to be one of the phenomena of socio-economic life. Thus the problem of studying imperialism, its economic characteristics, and its future, reduces itself to the problem of analysing the tendencies in the development of world economy.

What are these tendencies?

First, the comparison of firms’ labouring activities becomes more expansive. The formation of national prices signified that markets were levelling the field—calculating the social necessary labour time and disciplining companies to match or exceed the average efficiency in their industry and heightening the competitive tensions between individual firms. The formation of international prices intensifies this process. Entire economies become subject to the pressures of international markets and the “law of value”—the need to reduce the value of commodities. That’s why Marx and Engels described capitalists as “the leaders of the whole industrial armies” and workers as soldiers “placed under the command of a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants”. Capitalism transcends national boundaries in the search for raw materials, cheaper labour and new places to invest or sell products. The Communist Manifesto again:

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases [capitalism] over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere … The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which [capitalism] batters down all Chinese walls … It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the capitalist mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become capitalist themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

Just as an individual firm or a monopoly within a branch of production can make a super-profit at the expense of its rivals, or as an industry can accumulate a greater proportional share of the total value created within a national economy, in world economy, super profits can flow from one region to another. This is the law of value working as a transmission belt. At this level, the flow isn’t only about productivity, or of the cyclical shifts in supply and demand, however. Firms judge success by comparing their costs of production with their total revenues. In world economy, a series of variables, which can be absent or less noticeable in a local or national economy, are evident. For example, the cost of labour, the size of the population, a natural monopoly over particular raw materials, and proximity to transport or large markets can be decisive advantages in capitalist competition.

Second, the internationalisation of capital corresponds to “a reverse tendency towards the nationalisation of capitalist interests” as competition between firms becomes competition between national industries. It’s still the case that some firms close and others thrive in a particular industry and that labour and investment shift between different industries. But in world economy, investment shifts within the same industry but from one state or region to another. Bukharin argues that competition between them is relentlessly intensified, leading to a vicious struggle between national blocks of capital:

The destruction, from top to bottom, of old, conservative, economic forms that was begun with the initial stages of capitalism, has triumphed all along the line. At the same time, however, this “organic” elimination of weak competitors inside the framework of “national economies” … is now being superseded by the “critical” period of a sharpening struggle among stupendous opponents on the world market.

For example, we often don’t discuss the companies involved in competition—we talk instead about US steel, Japanese cars, Middle Eastern oil, Chinese batteries and so on. That is, we instinctively note that economic competition has geopolitical dimensions.

Third, monopoly tendencies increase because the scale of resources required to compete internationally reaches the greatest proportions. Where we had the development of industry monopolies within nations, the massive scope of the world economy and the intensification of competition lead to entire blocks of capital competing for access to the markets, raw materials and spheres of influence that collectively benefit the capitalists in one country.

Where businesses gobbled up businesses in monopoly formation, now countries incorporate other countries and entire regions of the globe. “The cleavage between town and country, as well as the development of this cleavage, formerly confined to one country only, are now being reproduced on a tremendously enlarged basis”, Bukharin writes. “Viewed from this standpoint, entire countries appear today as towns, namely, the industrial countries, whereas entire agrarian territories appear to be country.” Marx and Engels had already noted this phenomenon by the 1840s. But by the twentieth century, the scramble of the colonial powers had reached its apogee and most of the globe was incorporated into one of the empires, which Bukharin viewed as international monopolies of the highest order, reflecting the uneven development of countries:

The absorption of small capital units by large ones, the absorption of weak trusts, the absorption even of large trusts by larger ones is relegated to the rear, and looks like child's play compared with the absorption of whole countries that are being forcibly torn away from their economic centres and included in the economic system of the victorious “nation” … Thus on the higher stage of the struggle there is reproduced the same contradiction between the various branches [of production] but on a considerably wider scale.

Fourth, and inseparable from point three, the growing over of impersonal market competition into direct confrontation takes on a more extreme dimension in inter-state competition. Domestically, the state plays a mediating and disciplining role vis-a-vis businesses within its own borders. But this cannot be replicated in the global arena. The state becomes a much more partisan actor once economic competition between firms is displaced to international competition between national blocs. “When competition has finally reached its highest stage”, Bukharin writes, “... then the use of state power, and the possibilities connected with it, begin to play a very large part”.

State institutions monitor national productivity movements, contrast them with those of the rest of the world and make policy recommendations to governments. Importantly, richer states can finance industry research and development through their capacity to mobilise resources and take losses on a scale that only the biggest individual companies can. States might also manipulate the exchange rate of the national currency, giving all export industries a price advantage in the international market. All these things are done for a state to get more value flowing back to the country in national income. Sometimes, when a national industry’s productivity is lower (or its costs higher) than the global average, a government imposes import tariffs, artificially pushing up international competitors’ sales prices, enabling national firms to compete in the domestic market as though they were more efficient than they are.

Well before Bukharin’s time, Marx had written about the annexationist policies of the European capitalists and the exploitation and colonisation of non-capitalist areas of the globe such as Africa and India. Once most of the world had been carved up and a global system of production and trade firmly established, a state without many territorial possessions was at a distinct disadvantage unless it was endowed with abundant natural resources and an abundant domestic supply of labour to feed industrialisation. That posed the question of global re-division, which could occur only through confrontation. The result was the transformation of economic competition into military conflict.

Indeed, in the era of imperialist conflict, particularly World War One and World War Two, capitalists as leaders of industrial armies were replaced with military generals; workers as privates in those industrial armies were turned against each other as real soldiers. The heavy artillery of commodities was replaced with real artillery, not realising value but destroying it.

Bukharin noted—he was not the first or only writer to do so, but he was one of the clearest—that imperialism is the highest stage of capitalism. This notion is often taken to mean that once the imperialist epoch arrived, there would or could be no further changes to the dynamics of the world system. A more useful interpretation is simply that, at the level of world economy, there is no more “displacing” of contradictions and processes; all we get is re-division.

While local competition can be displaced to regional and national competition, once we arrive at “world economy”, there is nowhere else for the competition and contradictions to be displaced. The notion of an international state or world government would be plausible only if international competition were displaced higher again, to something resembling inter-planetary competition.

Trump and the logic of confrontation

Imperialism … introduce[s] everywhere the striving for domination, not for freedom. Whatever the political system, the result of these tendencies is everywhere reaction and an extreme intensification of antagonisms.

— Lenin, Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism (1916)

The United States capitalist class has no difficulty making money and accumulating wealth through the international trading and financial order it established and developed over the last 80 years. It controls the global financial system. Its companies make up 70 percent of the MSCI World Index by market capitalisation. It is home to 30 percent of the world’s billionaires. In recent years, its economy has outpaced those of other advanced states. So it comes as little surprise that most economists think Trump is bark-raving mad to blow up the very system that has provided the basis for American capitalist prosperity for decades.

Yet, as examined in note #4 on the US defence industrial base, the emerging consensus among imperial strategists is that the transformation of the US domestic economy since at least the end of the Cold War has left it at a serious disadvantage vis-a-vis China. Washington had one overarching national security priority after the collapse of the Soviet Union: to prevent a peer competitor from emerging. It failed to do so. Not only has Beijing developed the largest and most efficient manufacturing industrial base the world has ever seen, it has extended its advantages even in the face of Trump’s previous attempts to undermine it. The Lowy Institute in Sydney notes:

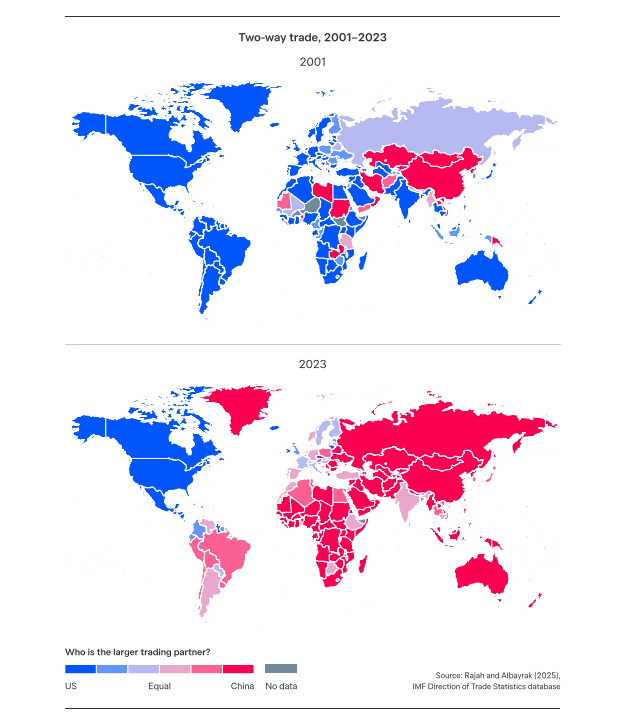

China’s lead over the United States in international trade relationships has only widened since the last US–China trade war of 2018–19. Around 70 percent of economies trade more with China than they do with America, and more than half of all economies now trade twice as much with China compared to the United States.

This is the conundrum of US imperialism. Trump isn’t blowing up the international order because he is economically illiterate—although he and his team may well be. He is blowing it up because the previous model might have made plenty of people rich, but it undermined the US industrial base (at least relatively speaking, but in some areas, such a ship building, absolutely) and enabled the very thing that US strategists had pledged to avoid.

The US ultimately broke the Soviet Union by using its vastly superior and more productive industrial economy to grind out the Eastern Bloc. It took decades, however, because Moscow erected an Iron Curtain—it sealed itself off from the Western economies knowing that its own industries would be put out of business if they had to compete in the world markets. The economic competition was displaced to political and military competition and an arms build-up that contributed to the Soviet economic collapse.

Now, the dynamic has been reversed. Perversely, “communist” China is heavily integrated into the world markets; it is the dynamic leader in manufacturing—the workshop of the world—and increasingly in other areas as well. And ironically, the capitalist US is building a new Iron Curtain of sorts (although its economic position is not at all as dire as Trump and the imperial strategists make out IMO).

At any rate, these developments cut against the sensibilities of the neoclassical economists for whom free trade is the basis of all rationality. Many of them don’t seem to even understand the problem of US imperial power—perhaps because they view the world primarily through the prism of $$$. But the logic of events today seems pretty clear. Bukharin outlined it 110 years ago.