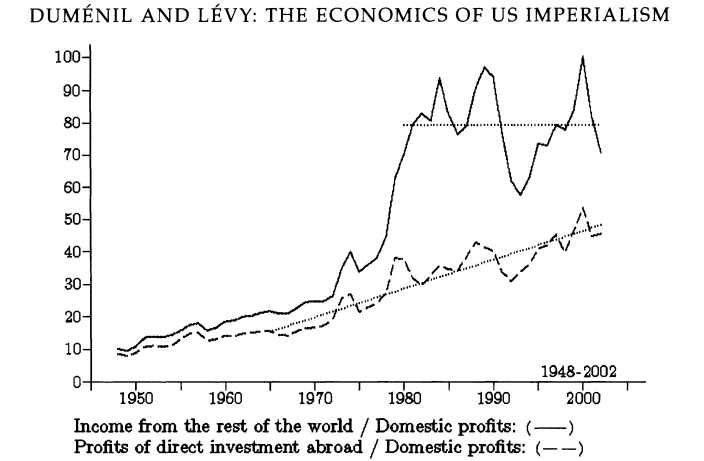

“For decades, our country has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike.” On Liberation Day, US President Donald Trump had me reaching for an old paper, by French economists Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy, estimating financial flows from the rest of the world to the US. As you can see in the chart below, the figure at the turn of the century was substantial. By their calculations, the ratio of total international capital income to domestic profits averaged about 80 percent throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

SOURCE: “The economics of US imperialism at the turn of the 21st century”, Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2004.

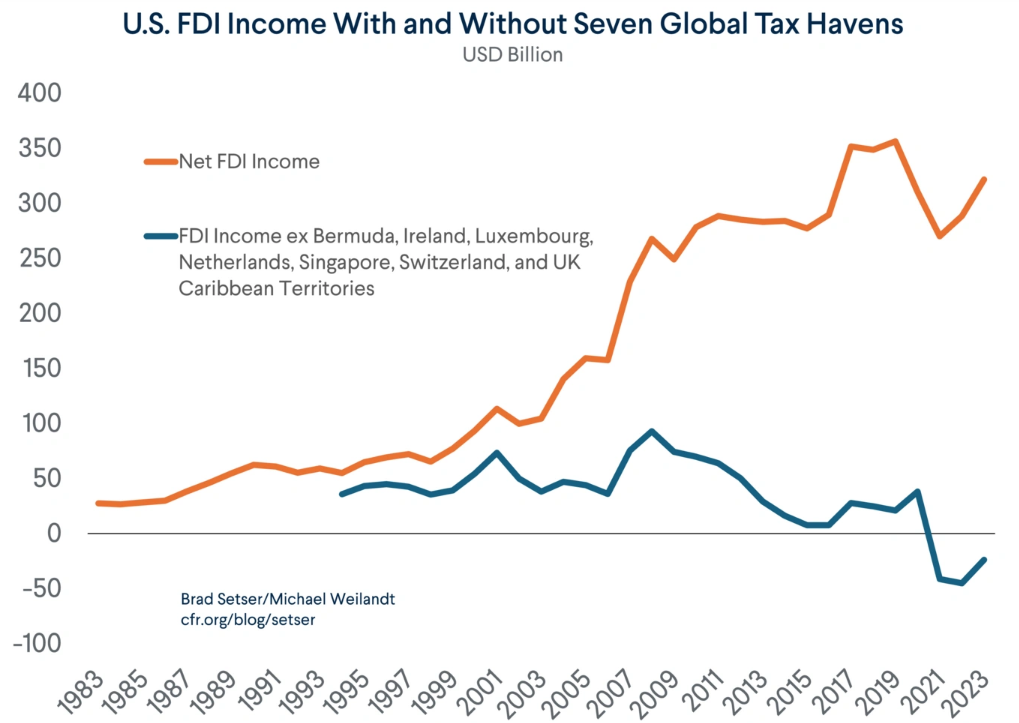

Duménil and Lévy wrote that the US was “pumping income from the rest of the world” through direct investments, portfolio investments and brain drain, among other things. They didn’t give dollar values, but those wouldn’t be difficult to figure out from the ratios they published. I had a quick look at more recent data tracking direct investment income. As you can see below, it increased in the years after Duménil and Lévy’s piece was published in 2004. The most recent data is from 2023, when total corporate income from the rest of the world approached US$600 billion annually. Subtracting capital income flows out of the US (to foreign companies with direct investments in America), the figure is still substantial: about US$300 billion in annual net income from abroad.

However, as a proportion of annual total corporate profits, which are about US$4 trillion, this appears much less than Duménil and Lévy calculated 20 years ago. Moreover, digging around for more recent analysis by corporate accountants, I stumbled on this piece by Brad Setser and Michael Weilandt at the Council on Foreign Relations. To cut a long story short, they argue that the positive net income flow is an accounting trick resulting from domestic corporations cooking their books:

The boring reality is that the income differential is now mostly a function of U.S. corporate tax avoidance—it goes away if the profits of U.S. firms that report earnings in the seven most significant low tax jurisdictions are taken out of the income balance.

So, once you subtract foreign incomes from tax havens, the US$300 billion positive balance becomes a net negative. And what appear to be proceeds from the exploitation of the world might be the untaxed profits from the exploitation of US workers:

At any rate, something related to all this in the Duménil and Lévy piece caught my eye. They argued (somewhat presciently in hindsight) that the US economy’s “major contradiction” was “the growing external trade imbalance”, which is the thing Donald Trump is so concerned about:

These deficits are due to the tremendous wave of consumption by the richest fraction of the population, which followed the restoration of the income and wealth of these classes in neoliberalism … [T]he growing disequilibria of the US economy—notably the external debt, and the debt of households and of the state—raise doubts concerning the capability of this country to maintain its unrivalled leadership.

Trump thinks the trade deficit shows that foreign countries are ripping off the US. Duménil and Lévy reckoned that changes in domestic income distribution and savings rates caused the burgeoning deficit. That is, the rich increasingly concentrating wealth in their hands was leading to a consumption boom among the ruling class, which helped to blow out the balance of payments:

The increasing propensity to spend on the part of the richest fraction of households appears as the main, continuous, cause of the decline of US saving rates and of the corresponding external [trade] deficits.

I’m not sure how plausible this is. On the one hand, as noted above, foreign incomes are overstated due to tax shifting, a situation that conflicts with their estimation of the “income pumping” from the rest of the world. On the other hand, it seems to confirm something of their argument about the role of the US ruling class—that its elevated consumption is part of the problem. Then again, much of the 21st-century trade imbalance in goods comes from mass-produced imports consumed primarily by workers, not the ruling class. So does that claim stack up?

The issue is too far outside my wheelhouse to attempt the accounting. But Duménil and Lévy’s incorporation of social class in their economic analysis of US imperialism (even if the authors’ definition of imperialism is dubious) makes their paper an interesting read IMO. You can get it here if you’re into that sort of thing.

[I’m reminded that I’ve had a book on my shelf for several years that purports to deal systematically with global value flows. I still haven’t read it, but perhaps it’s time to put it on the to-do list: John Smith’s “Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century: Globalization, Super-Exploitation, and Capitalism’s Final Crisis”.]

The bond market

There are other financial outflows from the US. Annual interest payments on the federal government’s debt are the most obvious. The national debt, which is growing by around US$2 trillion per year, is now more than US$36 trillion, some US$29 trillion of which is in the form of interest-paying IOUs called Treasuries (because the Treasury Department issues them). Treasuries come in bills, notes and bonds, depending on the repayment timeframe. For simplicity, all Treasuries are sometimes just called “bonds”, and the institutions and individuals who bought them—that is, who lent the US government money—are called bondholders. (The US Treasury market is just one component of a US$140 trillion global bond market, which includes corporate bonds and other government bonds, but let’s ignore that here.)

nnual interest payments on all federal debt now exceed US$1 trillion—more than the government spends on the military. Most payments go to domestic bondholders (the largest is the Federal Reserve Bank, which is owed nearly US$5 trillion). Almost one-quarter of the interest payments (US$240 billion annually) go to international creditors collectively owed US$8.5 trillion. The largest are Japan, China, the United Kingdom and Luxembourg. Most of the world’s pension systems and big institutional investors are also creditors accruing interest paid by the US government for funding its operations. (You could say that, by loaning the US government money, the Chinese government helps fund the US military. And by paying tens of billions in interest per year, the US government helps to fund Chinese advances in artificial intelligence. But that’s the perverse nature of the integrated global economy.)

When you hear about the bond markets “disciplining” Donald Trump, it means that holders of US government debt are offloading it, and new buyers/creditors are demanding higher returns. To grossly simplify this market movement:

Bondholder: “I’ve got a $10 million IOU from the US government. It will pay back the $10 million in ten years and, in the meantime, pay $400,000 per year in interest. I want to sell it to you”.

Bond buyer: “That government seems to have lost the plot and might be undermining its own economy. I’ll buy the IOU, but I want a 5 percent discount. I’ll only pay you $9.5 million”.

Because the US Treasury market is so big, because the bonds are so widely held and because nobody thinks that the US government will fail to pay its IOUs, Treasuries act as something of a reserve currency for the world financial system—perhaps US$1 trillion worth change hands daily. They usually provide stability and predictability. So if they are suddenly devalued, which occurred when Trump started the trade war, all the big institutions suddenly find that they are not holding as much reserve wealth as they thought.

Also, the US Treasury is forced to increase the interest rate on new bonds (it currently writes US$200-300 billion in IOUs every month), resulting in more financial outflows from the government to creditors/bondholders. That’s not ideal for an administration that says it wants to reduce spending.

Trump’s been hitting lots of people and groups. This month, financial capital slapped back.

US working-class incomes

While we’re on the topic of US incomes, the US working class is often said to be in a decades-long downward spiral or, at best, stagnation in living standards. The data doesn’t fully support this. The last four decades have, by most accounts, been hellish for swaths of the country. But, on average, it’s more like periods of stagnation punctuated by brief bursts of relief:

- 1984-1997 STAGNATION: In these thirteen years, workers’ real wages (the red line in the chart below) gyrated but ended up pretty much exactly where they started

- 1997-2002 GROWTH: Real wages up by 9 percent

- 2002-13 DECLINE: A drop of more than 2 percent

- 2013-21 GROWTH: Real wages grew at their most sustained rate in several generations, ending about 13 percent higher over eight years

- 2021-25 STAGNATION: After dropping again, they are today pretty much exactly where they were in 2021

Overall, real wages are nearly 20 percent higher than 40 years ago. Yes, that’s a pitiful growth rate for the wealthiest country in the world, but it is growth nevertheless, and most of it came in the last decade. Real median household income (the blue line) has grown faster, although that could result from more people per household being in the workforce or a range of other things. Nevertheless, from 2012 to 2019, there was a 23 percent increase in median household income.

I’m not suggesting everything is rosy for US workers. Last year, I spent days walking around Detroit; the destruction and destitution are horrible. However, this data on the wages/income boom beginning in the first half of the 2010s passed me by until recently. I was a bit startled by it, having grown accustomed to simply asserting the destruction of US working-class living standards over recent decades. I charted an OECD dataset showing the same trend in note #1 last year.

Einstein the socialist

Albert Einstein died 70 years ago this month. A few years before his death, he penned an article, “Why socialism?”, for the inaugural issue of the journal/magazine Monthly Review, right near the peak of McCarthyism and anti-Communist hysteria in the US. Here’s an excerpt:

The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. We see before us a huge community of producers, the members of which are unceasingly striving to deprive each other of the fruits of their collective labor—not by force, but on the whole in faithful compliance with legally established rules. In this respect, it is important to realize that the means of production—that is to say, the entire productive capacity that is needed for producing consumer goods as well as additional capital goods—may legally be, and for the most part are, the private property of individuals …

Private capital tends to become concentrated in few hands, partly because of competition among the capitalists, and partly because technological development and the increasing division of labor encourage the formation of larger units of production at the expense of smaller ones. The result of these developments is an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society. This is true since the members of legislative bodies are selected by political parties, largely financed or otherwise influenced by private capitalists who, for all practical purposes, separate the electorate from the legislature. The consequence is that the representatives of the people do not in fact sufficiently protect the interests of the underprivileged sections of the population. Moreover, under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information (press, radio, education) …

The profit motive, in conjunction with competition among capitalists, is responsible for an instability in the accumulation and utilization of capital, which leads to increasingly severe depressions. Unlimited competition leads to a huge waste of labor, and to that crippling of the social consciousness of individuals which I mentioned before. This crippling of individuals I consider the worst evil of capitalism …

I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.