Nazism emerged from a nation unable to stabilize itself and degenerated to unforeseen limits of depravity. The policy of aggression in Washington has brought a comparable degree of scientific extermination and moral degeneracy. The International War Crimes Tribunal must do for the peoples of Vietnam, Asia, Africa and Latin America what no tribunal did while Nazi crimes were committed and plotted. The napalm and pellet bombs, the systematic destruction of a heroic people are a barbarous rehearsal …

[T]he heroic are the oppressed and the hateful are the arrogant rulers who would bleed them for generations or bomb them into the Stone Age. The Tribunal must warn of the impending horror in many lands, the new atrocities prepared now in Vietnam and of the global struggle between the poor and the powerful rich. These are themes as old as humanity. The long arduous struggle for decency and for liberation is unending ... [and] necessary until the last starving man is fed and a way of life is created which ends exploitation of the many by the few.

Vietnam struggles so others may survive. The truths we must declare are simple truths. Great violence menaces our cultural achievements. Starvation and disease cannot be tolerated. Resistance at risk of life is noble. But we know this. Western Europe and North America are drenched in the blood of struggle for social change.

— From Bertrand Russell’s closing address to the Stockholm Session of the International War Crimes Tribunal (May 1967)

The War Remnants Museum in Saigon, Vietnam, is both a testimony to the incredible resilience of the country’s independence movement over many decades, and a reminder that all the contemporary handwringing about the purported demise of the “international rules-based order” is so much liberal imperialist cant; another attempted deception about the historical character of US foreign policy. The exhibits display the full range of war crimes carried out in the decades after the Second World War by French and American civilizing missions that left millions dead, millions poisoned by dioxins and a country—its economy, society, and natural environment—in utter ruins, with deaths, mutilations and poisoning from chemicals and unexploded ordinance continuing into the 21st century.

Some of the displayed images are so confronting it’s almost impossible to remain composed. A prisoner pushed and falling to their death from a US Army helicopter. Half-naked Vietnamese rope-tied by the ankles to US tanks, their bodies shredded by the rough roads and life ultimately dragged out of them. Platoon members proudly posing with the remains of independence fighters—who they’ve beheaded. A GI posing in front of a trophy skull, displayed openly on an army tent. An unarmed and stripped Vietnamese man lying in a ditch being kicked in the head and assaulted with a rifle butt as other soldiers look on. Rows of dead bodies. Another soldier, from the 25th Infantry Division, holding up a half a corpse—torso and head—what’s left of a resistance fighter blown in two by a grenade. Images of torture and wrenching suffering. My Lai, of course, features, along with testimonies of other massacres and atrocities for which justice was never served. Desecration after desecration. And then comes the room devoted to the effects of Agent Orange; a display evoking a feeling that humanity itself was poisoned and disfigured by the criminal Washington regime and its proxies and mercenaries.

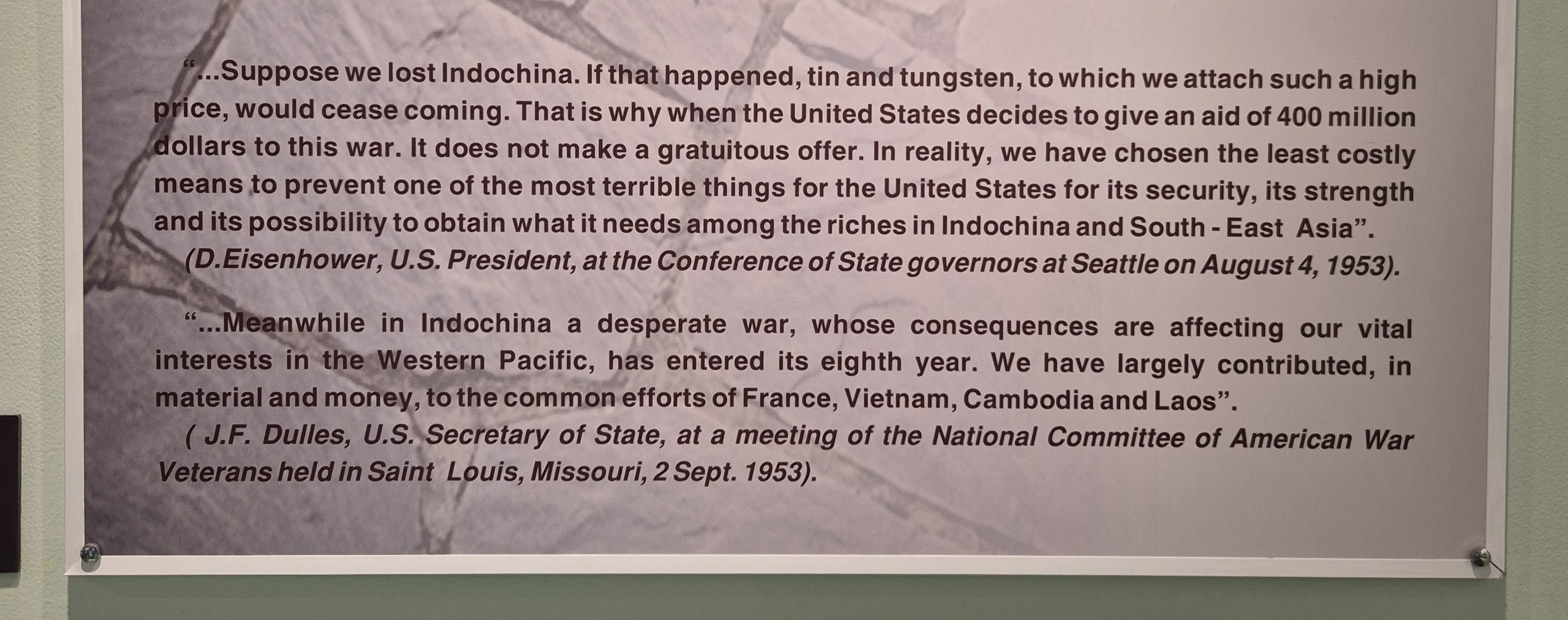

The original motives for US intervention were laid out in August 1953 by President Dwight Eisenhower during remarks at a governors’ conference in Seattle. Eisenhower’s Republican administrations wanted the French colonialists to crush the Vietnamese independence movement and its communist base as part of a shoring up operation for Western interests across Asia. The French failed just seven months later, their forces smashed by Viet Minh (League for Independence) guerillas. Ho Chi Minh formed a government in the North of a partitioned Vietnam; the US installed a puppet regime in the South, led by President Ngo Dinh Diem. The French went home to cry in their soup.

Many of the worst crimes committed against the Vietnamese came after this victory, during the heroic phase of American liberalism, first under President John Kennedy, who, by the time of his assassination in November 1963, had sent 16,000 military “advisors” to South Vietnam, along with special forces, and supported a military coup against Diem, who by now was considered unreliable; not hawkish enough, reportedly having attempted to make peace with Ho Chi Minh’s northern forces. It was Kennedy who began and escalated the direct US aggression.

Under Lyndon Johnson, fêted for his Great Society initiatives, things only got worse. By the time he left office at the beginning of 1969, more than half a million US soldiers were stationed in South Vietnam and atrocity was being piled on atrocity. Before Johnson’s time was up, the domestic glorification of the American cause led the country’s most prominent anti-war dissident, Noam Chomsky, to write of a “moral degeneration on such a scale that talk about the ‘normal channels’ of political action and protest becomes meaningless or hypocritical. We have to ask ourselves whether what is needed in the United States is dissent—or denazification”. (American Power and the New Mandarins.)

Any pretence that some “rules-based” order was being adhered to was by this stage flimsy to say the least. Indeed, much earlier, in September 1965, just six months after the first official batch of US combat troops landed at Da Nang, Oregon Senator Wayne Morse addressed the chamber:

In Vietnam, we have totally flouted the rule of law, and we have flouted the United Nations Charter … Ever since our first violations of the Geneva Accords, starting with the imposition of our first puppet regime in South Vietnam, the Diem regime, we have violated one tenet after another of international law and one treaty obligation after another, and the world knows it. For more than ten years, we have written on the pages of history with the indelible ink of US violations of the Geneva Accords of 1954, as well as article after article of the United Nations Charter and even article I, section 8 of the Constitution of the United States, a sad and shocking chronicle of our repudiation of the rule of law in our foreign policy practices.

Morse today is remembered for being a voice of reason, but his prime concern was for the reputation of the empire—he believed the US was losing its way, making it more difficult to maintain itself as the world’s leading power. For Morse, this was lamentable. Nevertheless, the charge of hypocrisy is relevant to the question of a “rules-based order” that US liberals claim to defend and uphold, even if it’s somewhat naïve to exhort a hegemonic imperial power like the United States to restrain itself through international laws and conventions. The reality is that the rules just disappeared when the Vietnamese refused to submit to imperial power.

There’s a broader point to be made. While the War Remnants exhibitions are primarily historical displays, it’s striking how contemporary much of it feels. For example, Eisenhower’s 1953 address appears no less transactional than the diplomacy of the current US administration, and offers scarcely any of the pious invocations of universal principles—or a proceduralism (say “a rules-based order”) purporting to be the basis of something intangibly greater than itself—that characterise other US justifications for military aggression:

Now let us assume that we lose Indochina. If Indochina goes, several things happen right away. The Malayan peninsula, the last little bit of the end hanging on down there, would be scarcely defensible—and tin and tungsten that we so greatly value from that area would cease coming. But all India would be outflanked. Burma would certainly, in its weakened condition, be no defence ... All of that weakening position around there is very ominous for the United States, because finally if we lost all that, how would the free world hold the rich empire of Indonesia?

Then there’s the revolutions of Richard Nixon, previously Eisenhower’s VP, who succeeded Johnson as president and began drawing down troops while expanding the air war into Cambodia and Laos. Nixon’s regime in hindsight feels remarkably Trumpian: an electoral realignment enacted through vile racism, a tariff and currency shock, detente with Russia and China (albeit more complicated today), the deployment of the National Guard against protesters (albeit by state governors), a belief among many on the left that the country was descending into fascism.

More pressing, though, in terms of the contemporary feel, is the reality of imperialist history repeating, with the same press narratives about good intentions, strategic mistakes and difficult choices ad nauseum; the same deadly outcomes and indifference to the human suffering caused by naked military aggression. The words used in 1967—“genocide”, “war crimes”, “complicity”—and on which Bertrand Russell’s tribunal deliberated and found to be appropriate in relation to Vietnam, were ignored or dismissed or denounced by government and the press, as they continue to be today in relation to Gaza.

So it’s the sense that Vietnam is Vietnow—which is why Russell’s words in Stockholm, quoted above, seems so apt. His warning that US was preparing a “barbarous rehearsal” to be replicated elsewhere echoed some French outlets’ concerns that the country was being used “as a proving ground and an experimentation field for the American science of destruction” (La Tribune des Nations, 4 March 1966). The words are displayed on one of the walls at the museum. As is the prescient note published in Le Figaro a year earlier, in April 1965:

Vietnam has become an experimental place for all inventions from US military engineers. Their purpose was to use living targets to test their inventions for later use in other battlefields.

So it was with the napalm, the Agent Orange and other chemical weapons, the carpet-bombing campaigns and torture regimes, the counterinsurgency manuals, and later talk about the need to “win hearts and minds”. (As opposed to putting millions in concentration camps, which seems to have been deemed a strategic failure in South Vietnam, though no-one had to answer for this crime, either.)

And so then came the US withdrawal, only for it to move on to operations elsewhere, such as those in Central America and the Caribbean—Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Grenada, Haiti and Panama—among other interventions in other places: “destabilisation programs”, coups, war crimes and ever more breaches of the so-called international rules-based order. Then Operation Desert Storm against Iraq in 1991, and, again, the testing of a range of equipment developed throughout the 1980s: laser-guided bombs, Tomahawk and Hellfire missiles, stealth fighters, new night vision equipment and surveillance technology—along with a brutal campaign of air warfare dumping more than 80,000 tons of regular bombs over six weeks and of course, reports of war crimes.

It’s hard to know exactly how many people have been slaughtered by the capitalist military-industrial complex in the post-Vietnam War era. Brown University’s Costs of War research in the 21st century, which estimates the human toll from US military operations and spending, notes:

An estimated over 940,000 people were killed by direct post-9/11 war violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, and Pakistan between 2001-2023. Of these, more than 432,000 were civilians. The number of people wounded or ill as a result of the conflicts is far higher, as is the number of civilians who died “indirectly”, as a result of wars’ destruction of economies, healthcare systems, infrastructure and the environment. An estimated 3.6-3.8 million people died indirectly in post-9/11 war zones, bringing the total death toll to at least 4.5-4.7 million and counting.

Again, many of these “interventions” involved direct contraventions of a range of international laws and conventions that liberal America still claims the country has been fundamentally committed to. Over and over again, naked aggression on almost every continent.

And then there’s Gaza, the modern laboratory and “experimental place” for military engineers. It may or may not be the worst atrocity of the 21st century, but it’s all the more condemnable for genocide being carried out and defended by a “civilised world” united in its attempts to destroy the basis of national life for an entire people. All the more condemnable for the Western liberal media and liberal establishment—again, the very same who lecture the world about international laws—being at the frontline of attempts to destroy the international solidarity movement with a devastated population.

Yet for all the similarities, a clear difference is obvious, illustrated by Che Guevara’s remarks to the 1966 Tricontinental conference in Havana, Cuba:

How close we could look into a bright future should two, three or many Vietnams flourish throughout the world with their share of deaths and their immense tragedies, their everyday heroism and their repeated blows against imperialism, impelled to disperse its forces under the sudden attack and the increasing hatred of all peoples of the world!

At that time, a growing sense of optimism was taking hold as the US seemed to be running aground: capitalism and imperialism were thought to be on the losing side of a brewing revolutionary upsurge. Hence the slogan “Two, three, many Vietnams!” caught on around the world. Today, we chant for an intifada in the absence of one. Palestine is a grinding slaughter, and Israel has come out stronger, not weaker, even if its mask has slipped. On the ground, Israel-Palestine is the opposite of Vietnam-USA. Yet Israel is empire, or at least a component part. And empires must eventually fall. But only under the pressure of two, three, many Vietnams, and two, three, many intifadas.

The War Remnants Museum displays part of this speech, but the curators have altered the original to make it appear as though Eisenhower was concerned almost entirely with Indochina, rather than also Malaya and Indonesia, and the broader “domino theory” that he outlined in Seattle: ↩